A Reader's List of Grinches and Elves

Characters who scowl and go humbug, or spread joy everywhere

Welcome readers, and joyeux noël.

Thinking over a couple year’s reading, (truth is, I’m not one of those lawnmowers who level a hundred books a year), I see more similarities than differences in the novels I’ve finished.

Along those lines, and in resisting the temptation to spit out everything I read this year like some one-upping chipmunk, I’m going with a shortlist.

Two, actually.

One list for adult-sized grinches—grasping, possessive misers who feel threatened by the freedom and happiness of others—and another for elves, ebullient Energizers who wear their hearts on a sleeve, hyperventilate, and fling joy and imagination wherever they go.

While I’m keeping these entries as brief and sweet as a sip of Kahlua eggnog, expect some small plot spoilers along the way.

And please, share, comment and keep the lists going with elves and grinches from books and movies you’ve come across!

Who else exudes elf-like positivity? Who’s good and ready to wipe every trace of Christmas from Whoville?

Who am I missing?

Grab some cocoa, drop your white elephant off, and I’ll get the party started.

First, the Grinches

Rodin Raskolnikov

Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Before, (and after) he murders a shrewish, old pawn broker with the intent of handing her small fortune to charity, the young, broke Raskolnikov creeps around St. Petersburg with a Grinch-like aura.

Just like the green fellow, he’s irritable, vain, solipsistic, and full of judgment for other people. He’s cold to his family, and ungrateful to Razumikhin, a pal who helps out while he’s bed-ridden with a fever.

And as Dostoevsky peels the layers back, we see the rot around the core.

Like too many nineteenth and twentieth century intellectuals, Raskolnikov believes his own foresight, goodness, and calling to advance humanity’s interests exempt him from respecting moral boundaries.

You know… ones like not murdering people.

In the end, and in what might be a delicious coincidence of translation, the raskolly-sounding name says it all.

Gene Forrester

A Separate Peace by Jon Knowles

Of all our grinches, Gene’s the studious one.

A straight A student at the east coast Devon school, we watch as Gene’s rivalry with his boisterous, athletic, rule-breaking roommate Finny turns deadly.

What’s fascinating, and closest to a green cave dweller who makes Christmas-smitten townsfolk into adversaries, is Gene’s ex nihilo creation of his own enemy mastermind.

Convinced that the physically dominant Finny is playing a secret game to hamstring his academics, Gene teeters into Cain and Abel territory. Soon, he sees everything, from Finny’s exhortation to ditch school and seize the day to their co-founding a club of daredevils who leap from a climbing tree into a river, as moves to hold him back.

While there’s much more to adolescence, the wartime setting, and Gene’s and Finny’s growth, it’s a memorable portrait of innocent rivalry dwindling into jealousy…and inner voices that echo Lady Macbeth’s advice to her murder-planning husband: ‘look the innocent flower, but be the serpent under’t.’

Watch out, Finny… and think twice before you climb that tree.

Edmund Pevensie

The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis

While Eustace Clarence Scrubb gets the trophy for having a ‘name he almost deserved,’ Edmund makes the list for his ill-temperedness. Like Gene Forrester, Edmund starts with rivalry, resenting the dictates of older siblings Susan and Peter, and getting his kicks by teasing Lucy, the youngest.

But we glimpse a cruel streak when Edmund throws Lucy under the bus. Like her, he discovers the iconic wardrobe that opens to a pine-frosted kingdom. But when a delighted Lucy runs back to the other two siblings, knowing that with Edmund backing her, they’ll finally believe Narnia’s real, Edmund laughs it off as a silly game.

Alongside the deep need to assert himself, Lewis shows that Edmund’s capacity for cruelty comes from self-pitying pride—something that the White Witch finds and exploits while grooming him in her sleigh with Turkish delight.

In a lurching turn that infuses the novel with grown-up themes of betrayal and transgression, Edmund sells out his siblings and defects to the witch’s side.

But unlike Mr. Grinch, who more or less rescues himself when he hears a Christmasless Whoville still enjoying itself, Edmund staggers back through bloodshed—only after the witch imprisons and humiliates him, and only because Aslan the Lion ransoms him through his own execution on the stone table.

In the final chapters, the penitent and forgiven Edmund fights valiantly with the risen Aslan, and takes his place on the four thrones with his siblings at Car Paravel.

No doubt a prodigal son, Edmund’s trajectory is a breathtaking portrait of what sin actually costs, and the foolish, unprecedented glory of God’s pardon for it by dying in a traitor’s place.

Because of Aslan, we, like Edmund, stand where everyone falls.

Maurice Bendrix

The End of the Affair by Graham Greene

The most textured of our Grinches, Maurice Bendrix is the bitterest.

He’s cunning, and charming to be sure, but singed with a jealousy that turns obsessive as we get to know him. When Greene’s novel starts, Bendrix tells us that he seduced Sarah Miles, the wife of his best friend Henry.

With the affair long over, he begins by calling it more ‘a record of hate than in love.’

His hate begins when Sarah decides to become a Catholic, which means leaving Bendrix and going back to honor marriage vows that turned stale long ago. While Sarah pivots toward unlikely sainthood, Bendrix clings on with death grip.

After Sarah’s death and the clear-cut miracles that follow in her wake, he sees himself in a ‘tug of war’ with a God he still doesn’t believe in.

“I sat up on my bed and said to God: you’ve taken her, but you haven’t got me yet… I don’t want Your peace and I don’t want Your love. I wanted Sarah for a lifetime and You took her away… I hate You as though You existed.”

Rather than growing three times larger, this heart shrivels to a lump of coal.

And Now for Some Elves…

Here’s a few spunky, wide-eyed characters whose lively energy is more contagious than omicron. If you need a gold standard, think Puck from A Midsummer Night’s Dream…or the character Joy from Pixar’s Inside Out.

Hands and feet inside.

Frankie Addams

The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers

In the play version of this sweltering, Southern novel, Frankie owns the stage with leaps and cartwheels.

A pre-teen tomboy with no friends and a distant father, she races around with shrieking war cries, contemplates the world in whimsical monologues, runs circles around her six-year-old cousin John Henry and the black maid Berniece, and picks at crusty black elbows with a hunting knife.

When her older brother Jarvis returns home with a glowing bride, Frankie’s mesmerized.

Before long, she’s in love with both of them.

For Frankie, who hatches a plan to leave town with the bridge and groom on their honeymoon and goes as far as stealing her father’s gun, the couple represents being known, loved, and included in all the ways she’s longed for—not to mention complete freedom from rules, snack time with John Henry, and Berniece’s pesky supervision.

It’s a fine portrait of raw and tender yearning, and one that actress Julie Harris hits out of the park in the 1952 film. With the painful disappointments of young adulthood built up like water behind a dam, we know this third wheel has a wipeout coming.

But who hasn’t dreamed of skipping town for exotic shores with the ones their heart admires?

Psyche

Till’ We Have Faces by C.S. Lewis

Lewis sets his robust spin on the Cupid and Psyche myth in Glome, a pre-Christian enclave in the chilled mountains of Central Europe. There’s freezing castles, hardscrabble villages, and dark, underground chambers where a priestly sacrifice animals to the gods.

Next to Narnia, Glome’s as harsh and foul as a D.C. prison block.

The narrator, Orual, is the oldest daughter of a King who resents her, mocks her, and takes every chance he has to remind her how ugly she is. Imagining she’ll never be loved by anyone, Orual finds her hair blown back when her father’s newest wife gives birth to a beaming daughter named Psyche.

Raised by the smitten, doting Orual, Psyche laughs and plays, gets lost in her own curiosity, and delights everyone around her with infectious, splendor.

Orual, whom Psyche calls Maia, can barely pin Psyche’s beauty down with words.

“It was beauty that did not astonish you till afterwards when you had gone of out of sight and reflected on it. It was the most natural thing in the world… she made beauty all around her. When she trod on mud, the mud was beautiful; when she ran in the rain, the rain was silver. When she picked up a toad—she had the strangest love for all manner of brutes—the toad became beautiful.”

Like Frankie Jarvis, Pysche longs for untainted and unreachable adventure—and to Orual’s horror, after her sister is offered up as a sacrifice to the gods and then left out past the kingdom’s boundary, Psyche finds it in a palace, a kingdom, and a mysterious, divine husband that Orual can’t even see.

As a result of Orual’s interference, Pysche shows elf-like resilience by completing the life-draining, impossible tasks the gods saddle her with.

But she echoes Aslan’s sacrifice by suffering for Orual, and then forgiving and embracing her in a final, near-death vision.

With untainted forgiveness, the beautiful Psyche saves best for last.

Swede Land

Peace Like A River by Leif Enger

Nine years old, and as sharp and precocious as Mattie Ross from True Grit, Swede shoulders wide responsibilities for the motherless Land family, cooking, nurturing, and looking after her weaker brother Reuben.

She’s a budding writer—both a poet and a journalist.

As the Land family searches the Great Plains for her older brother Davy, (a fugitive, running from the law after killing two sadistic bullies who broke into their home), Swede lionizes Davy by writing an epic ballad about an lawman-turned outlaw named Sunny Sundown.

Even though she hunts, takes charge, and helps keep a pesky federal agent from tailing then, Swede makes the elf list for her keenness, curiosity, and budding highbrow vocabulary.

On the subject of the miracles that follow their father Jeremiah wherever the family goes, Reuben defers to Swede’s understanding:

“My sister, Swede, who often sees to the nub, offered this: People fear miracles because they fear being changed—though ignoring them will change you also.”

This is no elf on the shelf.

It takes all of Reuben’s effort, (and ours) to keep up with her.

King Auberon Quinn

The Napoleon of Notting Hill by G.K. Chesterton

What’s more elfish than making all your dignitaries stand on their heads?

Or declaring that the neighborhoods of London will resort back to fiefdoms, each with their own armies, city walls, banners and insignia?

In a dismal future where everything’s convenient and consolidated, (even the throne rotates amongst random citizens), King Quinn rules for his own shits and giggles.

Though he eventually plays court jester to hero Adam Wayne, the only subject who takes the ‘Charter of the Cities’ seriously, King Quinn doesn’t even realize that he, himself laid the seeds of Wayne’s patriotic fervor years ago.

Not long before the fighting, Wayne tells him:

“It was your Majesty who first stirred my dim patriotism into flame. Ten years ago, I was playing on the slope of Pump Street, with a wooden sword and a paper helmet, dreaming of great wars. In an angry truce I struck out with my sword, and stood petrified, for I saw that I had struck you, sire, my King, as you wandered in a noble secrecy. You neither shrank nor frowned. You summoned no guards... But in august and burning words, which are written in my soul, you told me ever to turn my sword against the enemies of my inviolate city. Like a priest pointing to the altar, you pointed to the hill of Notting.”

Not half bad, and well within the tradition of pointy ears and gift-giving tomfoolery.

*If ‘Notting Hill’ sounds like it might be up your alley, I covered it in more detail earlier this year

Honorable Mention

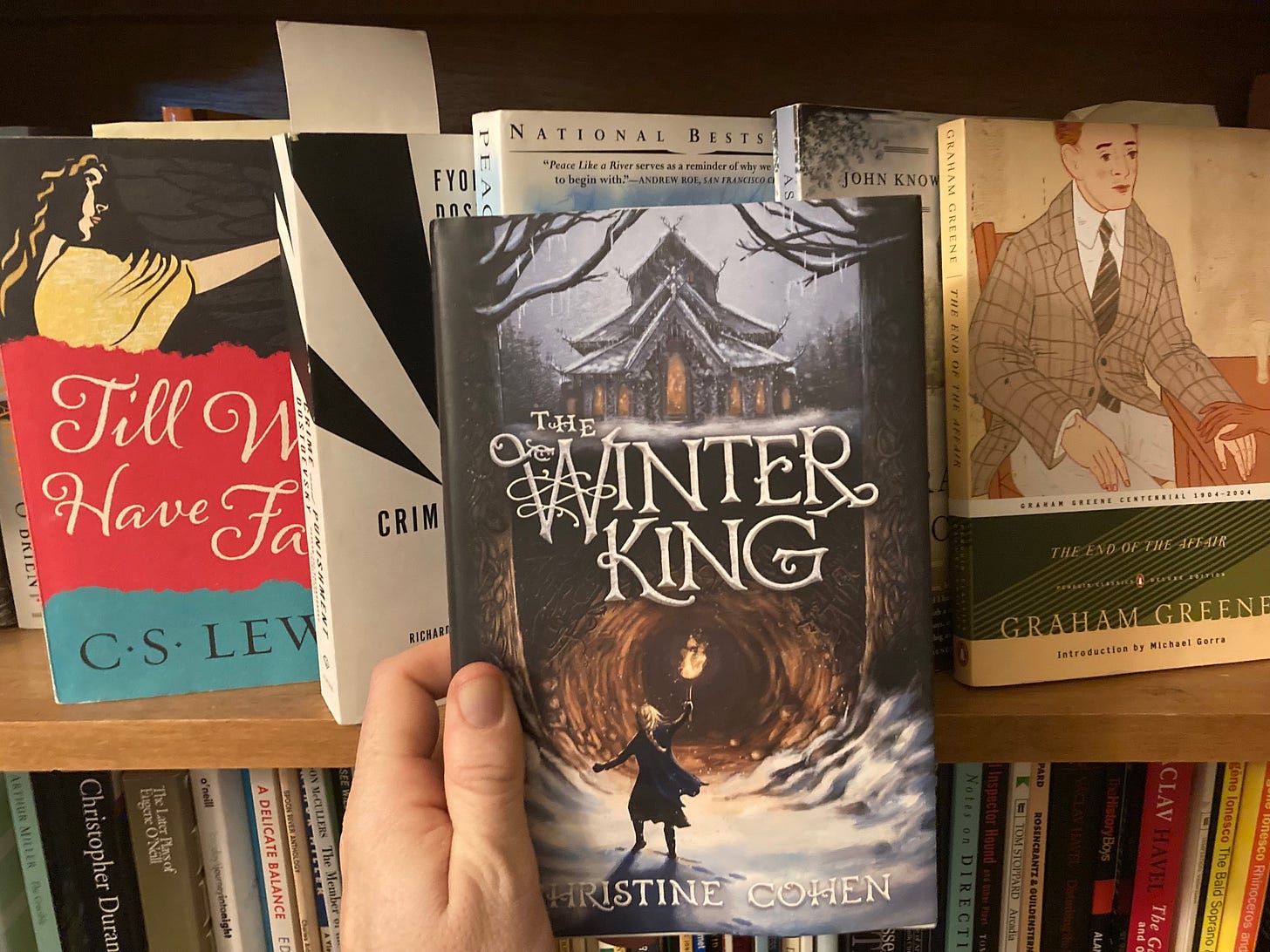

Before I sign off and hit you up for comments, I’m giving a honorable mention The Winter King, a frosty, bracing, fantasy novel by author Christie Cohen.

The elf is a young hero named Cora, a young villager who uncovers the secrets that just might save her impoverished family from the harsh winter.

Her boss—and tormentor—is a grinch named Nils.

If this shout catches your fancy, or if you’re already a fan of Christine Cohen’s spunky characters and haunting, far-off worlds, check out ‘The Sinking City,’ her latest offering from Canon Press.

Word on the Pond

I’m including the teaser because this is the only Crocodile coming out this month.

It’s been a swell year of reading and I’ll see you in January.

Warming up in the bullpen, I’ve got thoughts on Children of Men, Alfonso Cuaron’s 2006 film about a dismal future of worldwide infertility.

Much better than P.D. James’ original novel, the film jars us by laying out death and brokenness next to a miracle—an African immigrant who turns out to be pregnant.

Though it wasn’t written for a Christian audience, Children of Men is the most visceral adaptation of the Christmas story I’ve ever seen—and a bristling apologetic for the truth claims of the Christian hope.

More to come.

Thanks for reading and have a wonderful Christmas.

You’ve got me curious about The Winter King. Reading your posts always broadens my horizons. Merry Christmas.

You have a way of making me want to read at least half the books you reference.