Is ‘Squid Game’ Worth the Dive?

Thoughts on darkness, light, and zero sum survival.

Sometimes, and when you’re prone as I am to going from your newsfeed to a rabbit trail, you’ve got to weigh in on what’s twittering.

Coming off these last few weeks, the trails haven’t disappointed. But rather than discussing supply chain woes, vaccine mandate pushback, or Facebook’s rebranding as a trial version of the Matrix, we’re diving in the ocean…

Down to where glowing cephalopods flutter their tentacles.

For starters, I’ll give some straight review of the breakout show ‘Squid Game,’ an unashamedly violent nine episodes that show a mostly Korean cast of destitute lowlifes devouring each other for a cash prize, Hunger Games style. From there, we’ll talk landscape, skimming the murky waters of zero sum survival, semi-nihilism, and dog-eat-dog violence as a moral critique of capitalism.

To top it off, I’ll consider what the popularity of a Korean, non-promoted demolition derby suggests about (…you guessed it), our own cultural moment.

So as not to pull the old bait and switch on anyone, my bottom line is that ‘Squid Game’ is masterfully executed but not worth watching.

And while we’re down here in Challenger Deep, here’s your warning—heavy spoilers ahead, along with topical discussion of fact and fiction that might be hard to stomach.

So strap on the oxygen tank and hang on.

If you’ve heard about ‘Squid Game,’ the same show that straddled the number one download spot on Netflix and already sold an obscene amount of Halloween costumes, you probably know the premise. If you don’t, you can get the jist of it from SNL’s surprisingly funny Squid Game Country Song.

At any rate, here’s the set-up:

Four-hundred and fifty-six people, (the hero among them is Gi-Hun, a laid-off gambler and poor excuse of a Dad for his young daughter) accept a shadowy invitation to a high stakes game.

Each one of them, (or so we think) is desperate, miserable, and mired in debt—so much so that they’re willing to step inside a strange van filled with strangers. After a misty vapor knocks them out, they wake up in a warehouse-like dormitory.

Masked guards escort the crowd to a brightly lit arena with a large robot, dolled up like a schoolgirl, at the far end. The robot announces that the first game, one of six that will lead to someone winning $45 million, is ‘red light, green light,’ the stop-and-go race that operates like Simon Says.

When the robot chirps ‘green light’ they all run forward; when she turns her head for ‘red light’ high powered cameras, (in a devilish twist, they’re in her eye sockets) scan the crowd for movement, and automated rifles take out anyone who flinches.

Within seconds, it’s a massacre.

And by the time the traumatized winners return to the dorm, they’ve figured it all out.

The race to the cash will be a series of diabolical children’s games, each following a simple house rule—winners advance; losers die on the spot.

Horrified, half of the contestants vote to end the game, with an old man named Il-Nam, (he’s got a brain tumor, so he’s tagging along for one last thrill), breaking the tie.

Everyone goes home, and back to their problems…only to get back in the van a few days later.

Over eight more episodes, the games shift from speed and strength to cooperation, luck, and strategy—marbles, tug-of-war, cutting out a shaped cookie without breaking it, hopping across a glass bridge with panels that break, and at the very end, the ‘Squid Game’ itself, a sumo-style, one on one death match, played out across a circle, a square, and a triangle.

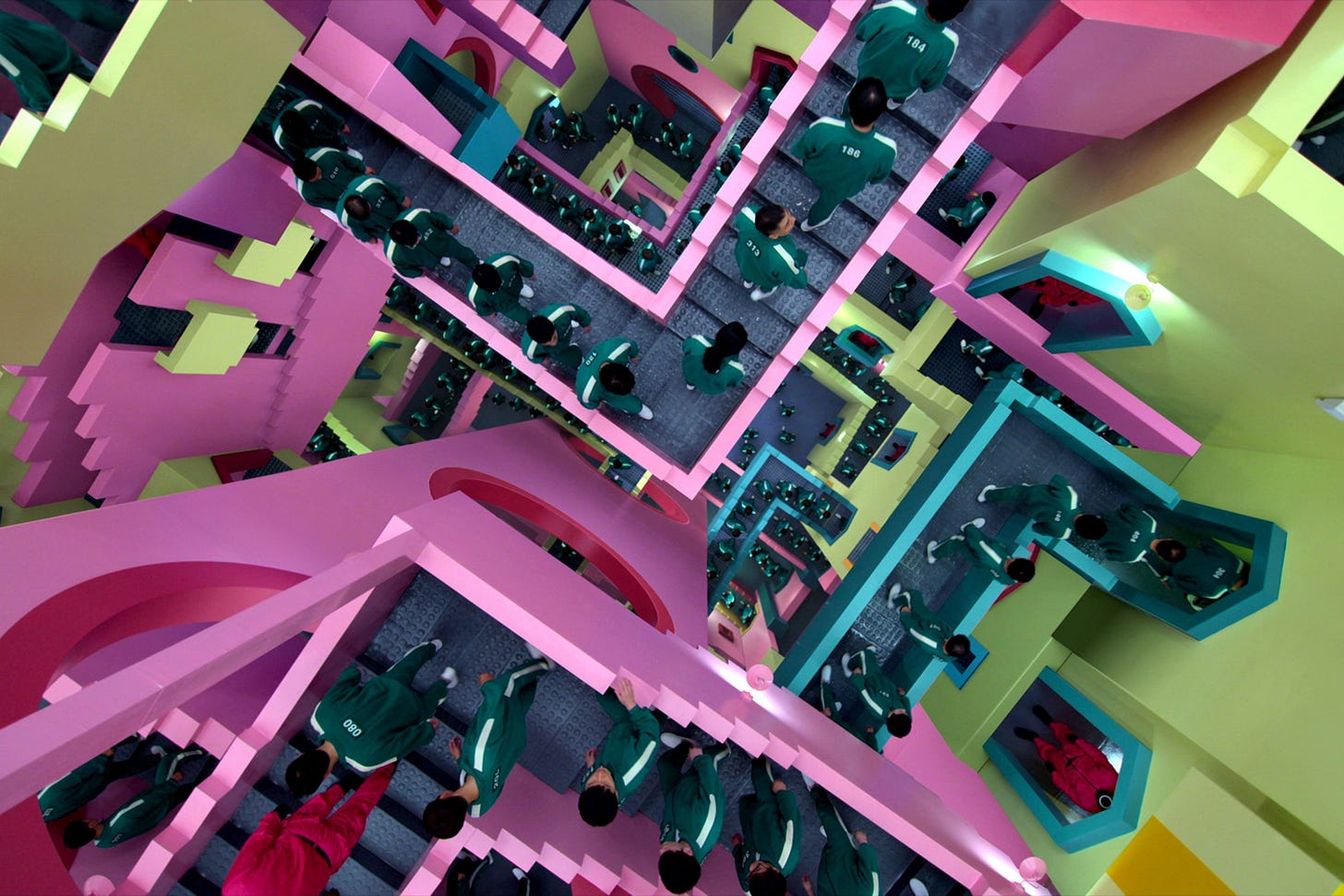

A colorful deathmatch

As the games play out with more and more violence, we watch a brief bloom of team camaraderie disintegrate into cheating, one-upping, and outright betrayal. When the players learn they can eliminate others from the game just by killing them, a faction led by mobster Jang Doek-Su starts a prison riot.

From there out, it’s dog-eat-dog mayhem.

Along with the brute realism, there’s enough tension, pacing, laudable acting, and visual craft to please those who can stomach the whole idea.

I’m not the first to notice the strikingly pastel colors of the killing arenas, player’s green uniforms, and the pink bodysuits worn by the guards.

The nursery colors are an obvious contrast to the gaudy gold and velvet of the V.I.P. viewing room, or the shadowy corridors where guards cart away losers and harvest their organs. The masked gamemaster called the ‘Front Man,’ is cloaked in black.

But for all the contrast, the show’s pitch black setup makes for some decent twists:

-Gi-Hun strikes an alliance with childhood friend Sang-Woo, only to see his pal’s cunning and determination turn to outright brutality.

-In a huge nod to The Hunger Games, wealthy V.I.P.’s fly in from around the world to watch (and bet) on which contestants will live or die.

-When a police detective infiltrates the compound, he unmasks the game’s ‘Front Man’ and finds out it’s his long lost brother, the winner of a previous Squid Game.

And one last spoiler:

-Il-Nam, the only player with unusually perceptive insight into each game—turns out to be the man behind the curtain, an ultra-rich investor who started the games decades ago as a gruesome laboratory to test out what humans might do to each other with the right motivation.

As far as plot, or even twentieth century history goes, Il-Nam needn’t have bothered.

There’s something to be said about reddit threads and you tube channels praising ‘Squid Game’s’ no-nonsense portrayal of gender, (with physically weaker women at a disadvantage to the men). Along those lines, there’s no trace of the diversity consultant’s stock characters—no racist villain, no Wonder Woman, no bullied LGBT sidekick with a heart of gold, and no brave, forthright BIPOC hero beating back racial prejudice.

Unlike nearly everything else being produced right now, the show doesn’t try to score points by veering into preachy, woke melodrama. In what seems almost like a nightmarish answer to what activists have been shrieking for, the game’s rules impose ironclad equality on everyone involved.

Win, or be killed—no exceptions.

Perhaps that’s no small factor in its rise to streaming stardom.

Rot in the architecture

My ‘Squid Game’ beef isn’t with the freewheeling violence.

Even where that warrants concern, it’s no Tarantino flick.

I’ll give Ben Shapiro some credit for calling out the show’s disingenuous caricature of free-market capitalism. To his point, there’s elements of that with the scrambling desperation, billionaire spectators, and characters drawn from the all-too-real stratum of Korean citizens hamstrung by debt. To top it all, a plastic piggy bank filled with the prize money hangs over them like a pinata.

But if condemning free market economics, (yet another exhausted Hollywood refrain) is the whole point, it’s a heavily ironic one.

Especially when the main events are all Russian Roulette—not models of winner-take-all capitalism but rather, un-shy depictions of the kind of games communist governments forced millions of their own citizens to play.

So that’s not the heart of it.

As with many shows that spin their own demented moral universe, mock the notion of objective good and evil, but then insist that good, evil, courage, and heroism are all real things… the rot’s in the architecture.

Along with a foul, briny smell.

‘Squid Game’ sinks because it piles corpse after corpse on the altar of a sad, false, underlying premise—that zero-sum survival (someone only lives because someone else dies) towers over everything else.

As an ultimate value—and apparently, the overriding reason why bottom feeders in South Korea’s ruthlessly capitalist ecosystem would rather take their chances in the Squid Game—survival becomes everything. But as the episodes show us, when it’s not anchored to something else, survival turns meaningless.

Concerned only with making it to the next round, the horrified contestants look away as others are shot, shanked, or pulled to their deaths in rooftop tug-of-war. While there’s plenty of shame and survivor guilt, it’s not enough to turn anyone’s animal instincts off.

Characters who choose to play for noble reasons, (a kind-hearted Pakistani immigrant who’s desperate to support his family, as well as a North Korean defector who needs money to free her mom from a human trafficker), get no special treatment. In a program designed to narrow down five hundred people to one man standing, their good qualities shrivel into liabilities.

In dog-eat-dog survival, the good fare no better than anyone else.

While a few characters sacrifice themselves, it neither changes the general equation nor stops anyone else from participating to the bloody end. And in watching everyone team up, kill, and let others be killed, we make our peace with survival of the fittest, a nihilistic vortex that rewards the strong or lucky, but swallows up any glimmers of heroism, courage, or meaningful sacrifice.

Anything resembling God’s character, or the qualities God-loving people should develop as they navigate a fallen world, doesn’t apply.

Doing darkness well

None of this is to argue that good stories, ones that affirm what’s wholesome, true, and beautiful can’t crawl the depths.

Like Alfonso Cuaron’s incredibly bleak but ultimately hopeful Children of Men, dystopian nightmares can pierce darkness with a ray of hope. Or, like the sparing examples of Dostoevsky’s Demons, Shakespeare’s Macbeth, or Orwell’s 1984 they can affirm that darkness is indeed, bottomless—and that even those standing at the bottom of a well can see light, truth, and forgiveness glimmering overhead.

To steal from Saint Augustine, light is light, and darkness is light’s absence.

But we run into problems in worlds that confuse light with darkness, or suggest that light and dark are meaningless, grayscale, or not what we think.

Unlike 1984, ‘Squid Game’ doesn’t work because every hero, even after opting out it, returns to the meat grinder and rides it out.

Though the voluntary nature of the bloodshed make ‘Squid Game’ more sophisticated than the likes of the Saw franchise, (which spin torture and bloodshed as a flimsy way for kidnapped characters to pay for their sins), it’s no Christian tragedy.

Where Macbeth shows an individual sinking to final condemnation for truly evil deeds, watching people voluntarily risk everything in a game where everyone but the single winner dies blurs all categories.

It’s survival with callousness, a toxic blend that kills the soul, if not the body.

Gi-Hun, like Katniss, (as Brian Kohl and N.D. Wilson point out in their Stories are Soul Food podcast), is tainted because he participates whole heartedly, knowing what will happen.

His attempt to stop the game at the very end when it’s just him versus his friend Sang-Woo is almost cute. Mortally wounded, Sang-Woo, implores Gi-Hun to take care of his dying mother and then kills himself, forcing Gi-Hun’s win by default.

That Gi-Hun is haunted, broken, and unable to even touch his $45 million doesn’t change anything.

In an a somewhat meme-worthy moment, he decides not to board a plane that will take him back to his daughter in the United States. With the steeled look of someone on a mission, he turns back and crosses the terminal—presumably to go back and end the Squid Game once and for all.

Too little, too late.

If it’s a last second reach for courage, righteous anger, or moral purpose—and not just a clickbait promise of more slaughter to come in Season Two—then it’s a slimy grasp at what the show itself has rendered nonexistent.

Or at least powerless when it comes to surviving in a world where the only thing worth living for is a hefty fortune.

“In a sort of ghastly simplicity we remove the organ and demand the function. We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honor and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.”

-C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man

Stories build loyalties

Even though we’ve been in the habit for a while, buying into imaginary worlds where the only thrill is identifying with the lucky sap who’s still alive brings consequences.

You don’t have to look to far to find obsessive survival at the cost of someone else.

While I’ll leave you to make your own connections, I will touch on the rise of normalized shoplifting, property crime and violence, often in broad daylight, and often with model bystanders who, from fear of a lawsuit—or in the case of store clerks—instant termination, do absolutely nothing.

Without going into detail, a Philadelphia woman was raped on a moving train earlier this month. In a description that’s still being contested, but sounds like it could have made ‘Squid Game’s’ director’s cut, bystanders came, left, filmed some of it on their phones, but did nothing.

Even granting that some were probably not on the train long enough to grasp what they were seeing, incidents this tragic beg a jarring question:

Which stories do we want to be in in?

And who in the story do we want to be? Those who make a fetish of herd safety and personal survival but won’t step in to help a real victim?

Or rather, as the still unfolding stories of those who rushed into Towers One and Two on September Eleventh remind us, do we want the loyalties of those who respond with courage, action, and a readiness to sacrifice if it might tilt the scales for someone else?

If stories, like meal ingredients, feed our souls and loyalties, then it’s time to think carefully about what we eat, and ask ourselves if survival over everything else is really the message we need to hear.

In this case, steer clear of seafood.

Stellar review...send me one of them stickers so that I can go put it up on a lamp post somewhere.