In my best impression of a Paris Review preamble, I’ll lay some groundwork for this author interview with Ian Duncan, the first of its kind on Shelf of Crocodiles.

While Ian dignified our zoom chat with a glass of bourbon, I’m swapping out glass screens for a more fitting background—the weekend before our first residency at New Saint Andrews College, when I first met the tree-cuttin’, memoir-scribbling Virginian in person.

The Introduction

I remember stepping off the bus and breathing in the chilled, northern air. A coordinator for our newly minted M.F.A. program welcomed me into his truck and shuttled me to a motel room that the college had generously arranged for the night. Word was, I’d have a roommate—a fellow first year whom I’d exchanged pleasantries with online.

When we opened the door, someone inside towered to the ceiling.

With a deep, resonant voice that called to mind the Wyoming plains or the Rocky Mountains—and one I’d hear reading bedtime stories to three offspring over facetime that week—the giant introduced himself.

“I’m Ian. Pleased to meet you, brother.”

The handshake was solid.

As we walked an outlying road to the town’s main thoroughfare, where a fellow student and her husband owned a taphouse, I got the feeling nobody would be leaping out to steal our wallets. Not in the presence of a six foot three woodsman who once worked at a gun store—or someone whose daily workouts involved climbing maple, pine, and dogwood trees and then slashing them to the ground one chunk at a time. A year and a half later, Ian would mail himself a chainsaw for a tree job in town, only to be stopped by a pounding snowstorm.

Over sips of imperial stout, Ian proved curious, sharp, thoughtful, and prone to laughing with a wide grin. While our program required us to finish a novel over two years, he’d already churned out three.

Who was this guy?

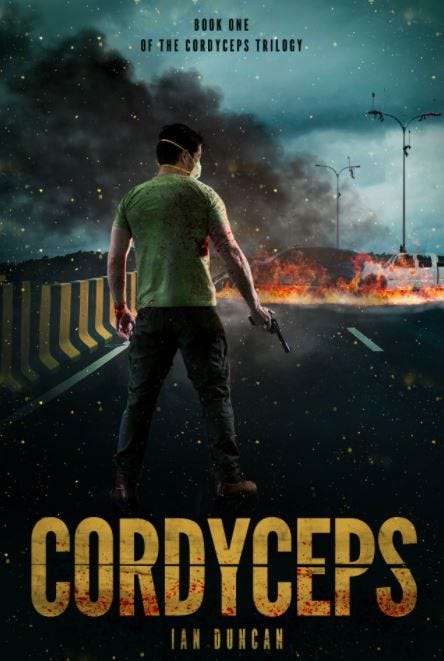

That evening, Ian told me about writing the Cordyceps Trilogy, three bio-thrillers about a zombified population that climbs buildings and light poles to shower the air with infectious spores.

The books have a decent following, and they’re all the more jarring because, if you ask the ant populations of Brazil, Thailand or the Florida everglades, the cordyceps fungus is a real thing.

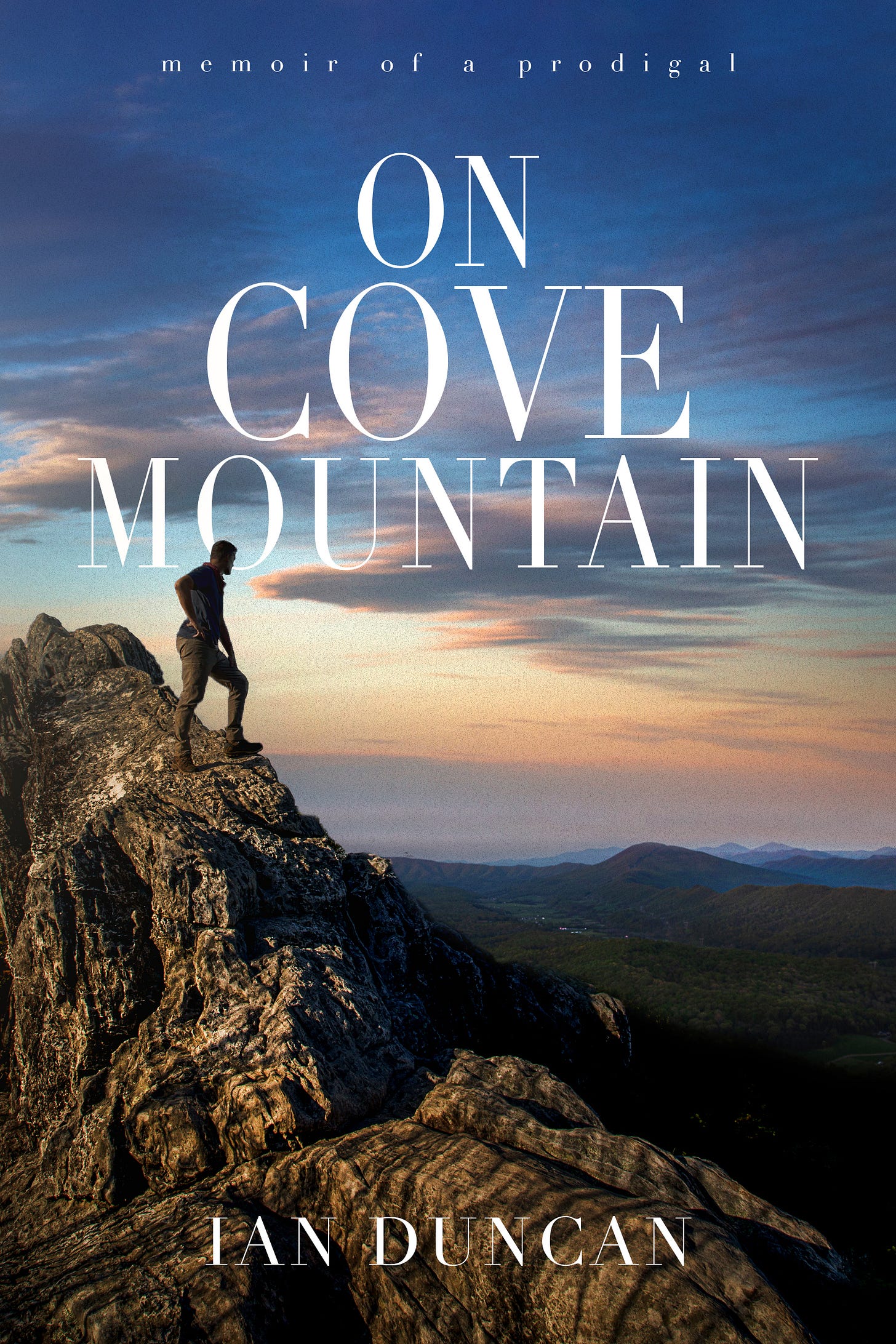

But if survival dominates his first three books, Ian’s fourth, 'On Cove Mountain' takes the subject deeper, diving headfirst into the author’s own struggles, discoveries, inner demons, and his confession-beaten path home.

Like his other book title, ‘Cove Mountain’ is also real—a lookout ridge on the lower Appalachians that Ian’s been hiking for decades. It’s an idyllic spot for feasting on the sights, sounds, and wildlife outside Roanoke, as well as a recurring locale in his memoir; a lighthouse for the stormy seas of a turbulent young adulthood that echoes the parable of the Prodigal Son.

Over two-hundred and eighty pages, we find Ian hauling building supplies, breaking hearts, backpacking, getting caught on the mountain in a blistering storm, writing his guts out but getting rejected from ten graduate programs, meeting his bride-to-be Allison—and in a searing opening chapter—banging against the padded doors of a room in a mental hospital.

Having known Ian as a friend since that walk into town, and having heard some of the tales in his memoir firsthand, you’ve got it on good authority—from lookout to valley, his coming of faith story is as true and piercing as it is unforgettable.

The Interview

In his own words, Ian Duncan.

(The Crocodile) What are you writing about these days?

(Ian Duncan) It’s been such a busy season, and one full of such significant events for us. My only goal has been to spend time journaling, just to sort of hit the record button on life. My wife’s about to have a baby and we’re considering a cross-country move to take a teaching position, and so we’re living with the awareness that everything might change. I’m going to want to remember this season. It’s going to be one of those stories of people that uproot everything and go to a new land for a fresh start.

Watership Down?

Ian laughs.

Almost. Maybe if Youngkin hadn’t won the governor’s race.

Are your journals written out longhand?

Yeah, I’m old school and leather-bound. I just write it up with a pen. No batteries, no wifi, no software updates. That’s the best.

Let’s get going on Cove Mountain. Why memoir? And where did all this prodigal son stuff come from?

It’s interesting because this is actually my second memoir. The first was more of a family memoir, so I was telling stories that were not only mine, but that also belonged to other people. And it turned out there were people in my family who were upset by some of the stories I shared.

That’s right, you told me about that.

Yeah. And I was really stoked the first memoir. I thought it was the best thing I’d ever done. So I was up against this sort of dilemma—how can I proceed with this when, it feels like I’m choosing between my career and my family? I decided to shelve the manuscript and wait, maybe ten years, maybe twenty. I still think it’s a story that needs to be told, but not just yet.

So Cove Mountain came on the heels of your first attempt.

Basically. When I turned around and decided to write another memoir, I knew it was going to be a story that only I owned, and that no one could say anything about me publishing… if I remember correctly that was in the works about the time I got accepted into the MFA program.

This was the first time you’ve recorded an audiobook too, right?

It was. I had a lot of fun with it and, I’d never done that before. It seemed a very natural fit… to read this story, my story, in my own voice. People have said the audiobook is their favorite form to read it in. For me, it renewed that sense you have as an author that you’re giving your story to each of your readers. Here, I made this for you. That’s very significant.

“This one is really crazy,” they say.

I give up with the floor drain and spend the next several minutes running at the steel door, ramming it with my shoulder, screaming—unconvincingly, no doubt—that I am not crazy. They unlock the door and burst into the room, hesitating just inside it, bracing themselves for my attack. Behind them, framed by the open door, is the sort of long white hall I will see in my nightmares for the next five years…

This is the furthest I ever got from Cove Mountain.”

You start the memoir confined in a Texas hospital; a visceral beginning to say the least. Was that opening sequence difficult to write? Easy? Cathartic?

It wasn’t difficult to write that part of it. The difficult part was practicing telling the story for seventeen years before I had healed enough personally that I could tell it without, you know, my heart racing and my breath coming up short. There was certainly real trauma involved. I guess you could say the ability to write this was the fruit of a long healing process.

In terms of pacing and sequencing, Cove Mountain flows, trickles, and then a dam breaks and a flood comes rushing out… how was flexing those memoir muscles different from writing fiction? Or did the storytelling feel similar?

There’s some real similarities. It’s kind of surprising how much of your fictional storytelling skills, or your story architecture skills come into play assembling the narrative that just happens to be nonfiction. But how you decide to tell the story, and how you arrange the chapters and scenes, how you begin, how you end, and how you move the narrative along… all those things are driven by the same story architecture that you find in fiction.

Makes sense.

It’s a bit unnerving, too. You have all these components that really happened… but depending on how you arrange them, you can make the story seem very different. It’s sort of like you’re tinkering with history… It gives you pause, and it should, because it’s a very powerful set of tools at your disposal.

Right.

That was the whole problem with my first memoir. No one was disputing the facts I was telling, it was the way they were arranged. And so… you start getting into all these layers. There’s objective history as only God knows it. Then there’s what we manage to remember and record, and by now we’re already getting into personal differences. I remember it this way, You remember it that way. So there’s all these layers of story that you have to reckon with in a memoir.

When they see the label ‘based on a true story,’ people go, ‘oh, this was real. Every single thing.’ But not necessarily. It’s all work and intentional structuring.

Yeah, you’re arranging scenes and if you’re doing it well, then you’re doing it deliberately. I can’t imagine anyone telling the story just blow by blow as it happened with no dog in the fight.

So ‘lost and found’ was your intention from the start.

Right. I wanted the book to be centered around Cove Mountain. The mountain was both a setting and a character. So my time in Texas, even though it was four of the sixteen years the memoir covers, was only treated briefly. And I was careful to tie those years closely to Cove Mountain. So I talked about how I searched for alternatives to Cove Mountain in the city, you know, like hiking up the steps of the parking garage again and again. So even though I’m in Dallas, a thousand miles away, we’re still talking about Cove Mountain.

So you were layering memories over other memories with your theme as the foundation. Kind of like a north star for the voyage.

Yep. And if you think about it… if memoir was just autobiography, then everyone would only have one memoir to write. I was born, I lived, I died, the end. But memoir, particularly the way Annie Dillard does it, is more creative meditation than biography. And it’s something you can do again and again, which is more exciting to me. It’s just life as I encounter it, recorded in my own voice. You don’t have to be a celebrity, you don’t even have to have a sensational life—that is, unless you’re vying for some big publishing deal. All you have to do is be someone one enjoys thinking deeply about life, turning things over, analyzing them, and doing so in a way that’s enjoyable for other people to read. That’s memoir. That’s all it is.

“I left my first serious girlfriend in the middle of a ski trip in Utah. Just called a taxi and left in the middle of the night. Just so you know, that’s not a thing manic depressives do; that’s a thing assholes do.”

Absolutely. And in your case, you can even spread it out with the detail of a Jon Krakauer, or an Annie Dillard… or the observation of a Bill Burr, depending on the passage.

Ian laughs.

Yeah, Dillard and Krakauer are some of my favorites. I actually read a lot more nonfiction than fiction. I honestly think I could live without writing another novel. But I don’t think I could live without writing, say… journaling for the rest of my life.

Going back to your journaling, it sounds like it’s ammunition for your nonfiction.

It is. But the older I get, the more exciting memoir is for personal reasons. I’ve come to realize how beneficial it’s been for me to organize my thoughts, to write things down, to record memories… especially now that I’ve got three kids and another one on the way. So I’m writing about the things they said, the funny stories, the things that I would have honestly forgotten. Even though my journals were the source material for my memoir, they’ve become a lot more than just a workshop. They’ve become a family photo album, an almost archival significance in our family. I’ll read something back to my wife from two years ago. I’ll read her an entry out loud and she’ll say, ‘I’d forgotten that. I’m so glad you recorded it.’

What kind of responses have you had to Cove Mountain so far?

The number of people who have come out of the woodwork and said they were inspired by this book to write down their own story, that’s been encouraging for me. Because it can really be a cathartic and important experience for people.

That’s wonderful.

Yeah. I mean my story’s really not all that unique in terms of people with mental illness, or people who have had traumatic experiences. One of the main things I wanted to accomplish with Cove Mountain was for readers to realize that we gain nothing from hiding our stories, but we gain so much from telling them. Because honestly, America’s a very mentally ill nation… I’ve been surprised how many people have said, ‘I also was committed,’ or ‘I was on those same medications.’ You want to talk about a pandemic, take a look at mental illness.

Have you heard from anyone who thinks you’re wearing your heart on your sleeve a little too much?

No doubt some people have that response. Typically, they’re not the ones you hear from, though. This is actually one of the things I like to get up on a soapbox about, because I actually went through this transformation when I moved to Texas. Almost accidentally, I transformed from a Person Who Hides Their Story into a Person Who Tells Their Story.

What did that transition look like?

I was making a new start for myself, in a new state, in a new town, and the question naturally arose: what will I tell people about my past? Up to this point I had kept as much as possible private. But very slowly I began to experiment with telling some of my new friends some of the stuff that had happened to me. I was at seminary, so I was surrounded by all these friends who were aspiring pastors, ministers, teachers—a very safe place to attempt that. And when I did, the response was amazing. Some of that feedback gave me the courage to practice telling my story.

Was that long before you opened a word doc and started typing?

So the book was actually the last step in this process of learning to tell my story. I remember how, in those early years my heart would race, and I would be short of breath trying to tell people the story over dinner, at someone’s house. But that’s something you practice. So all those attempts are really the first draft of this story and the book you have in your hands is the last draft. For a while, for years, I was just too close to the story to do a good job telling it. A big part of the healing process is telling the story over until you’re not telling it for your own catharsis, but for the benefit of others.

Because it only benefits others when they see your common humanity and they can learn about themselves from your story. It’s not that some freakish thing happened to you and your life’s a tabloid…. it’s more like ‘in you, I can see myself, I see other people I know, I see my own tendencies toward these things. And I can change, I can learn, I can do better, because you had the courage to tell your story.

And that’s the best part of this.

So if you go back to your breakdown at age twenty, when you start the book in a mental hospital, the healing from that point on often looks like slow, careful practice.

Not always.

Ian laughs.

There’s a funny story in the book, recounted by someone I’m actually good friends with now… he saw me out in public in the early months after I’d been released from my commitment, and he says I actually ran from him in public to keep from having to talk to him.

So that’s where I started, you know. Utter shame and brokenness... running from old friends so I wouldn’t have answer awkward questions about what had happened to me. So I went from running from people to publishing a memoir with ALL the details. But that’s what eighteen years can do for you. That’s the healing process. We think we’re doing someone a favor by not asking someone to share painful stories... but it only makes it harder for that person to re-integrate and to learn how to tell their story and move on with life.

Your book stares faith and doubt right in the face. But ultimately it’s a homecoming, a story that boomerangs to hope and redemption. Are you writing to encourage others who are struggling with their faith or perhaps have lost it?

Yeah, it’s definitely a book for prodigals. It’s also about God’s faithfulness in being the hound of heaven that doesn’t give up on his people but pursues them with undeserved mercy and kindness. It’s a chronicle of that. The redeemed of Christ will say, peek into any portion of their life and you’ll find it’s a record of God’s faithfulness, even in the darkest times.

That’s quite a rung to hang your story on.

Lost and Found become these sort of bookends for me—bookends that turned out to be eighteen years apart. And that’s something I never would have imagined… that God has the patience to develop a story in our lives over periods of time when we work so hard to put it behind us and bury it. And yet, he’s working to bring about real healing. And I guess that’s the thing for me, real healing has got to be not just burying something so deep down you never have to deal with it again, but getting to the point where you can share.

Much different from wearing pain or victimhood like a badge.

Yup. And of course, we’re a society that likes to medicate and to cover things over with serotonin intake inhibitors… but there’s very little closure to any of our problems. We don’t even offer people the hope of that. You know, you’ve got AA meetings telling you this is your identity. You’re always going to be an alcoholic. You’re always going to be a drug addict. You know, ‘Hi I’m Ian and I’m an alcoholic.’

Hi Ian.

And that’s it? That’s all the hope you have to give people? You know, that’s pathetic. As long as you’re, you know… functional you’re okay. Well, that’s not much redemption to offer people. And Christ has this incredible real healing to offer. Real closure, real healing, real, you know… soul-mending closure to a story like mine that the world just… knows nothing of. I think that’s the hope we have to offer in Christ, to a world full of mental illness and the effects of sin, we can offer this. We can do much better.

So, talking about healing bookends… I love that you put it that way, and I’m getting melodramatic here… did writing about when the judge finally cleared your record, or when you first met Allison in the coffee shop bring any moments of positive catharsis that broke on through?

Absolutely. That’s a really good insight. Because, yeah… the old trauma’s kind of faded… and the thing that hits me with more emotional weight now is exactly what you’re saying. It’s that realization of God’s faithfulness and seeing how the story ends. It’s standing on that mountain top now and looking back over all those twisted trails, seeing God’s faithfulness and seeing what he’s made of my life after I surrendered it to him; that’s what hits me with emotional force now. And there were definitely moments of typing with tears in my eyes.

I remember when I first finished this draft, my wife and I were actually on a road trip and I read it out loud to her. I pretty much broke down at certain points, just reading it out loud. It definitely has more force… and I think some of the structure surprised me. You know, we talked about how the writer’s choices arrange the story... but this was like discovering structure that God himself had put into my life.

Well, He’s quite the author.

He is. And recognizing the sorts of bread crumbs he leaves in your own life, the sorts of symbolism and coincidences that are definitely way more than coincidences...seeing those things in your own life is a powerful experience.

“We danced in the late summer heat, a live band playing, and in that blur of faces and twinkling white lights it seemed we had called together some vision of the afterlife, of the saints gathered around us, the only requirement for their admission full joy in this union, at last, of bride and groom.

We dashed down a gauntlet of friends who pelted us with diced rosemary and lavender; I remember pulling Allison by the hand… and taking a full blast right in the mouth as I was yelling something.”

Does any bookend stand out?

For me it was appearing before a judge, and being expunged of the thing I was most ashamed of in my life… I couldn’t have made that up. I couldn’t have come up with a better metaphor for the Christian standing justified before God. But when you’re journaling day to day, there doesn’t always seem to be those connections...you don’t always get the sense of your life as a flowing narrative until you assemble it into one and then find, low and behold, it actually flows.

Sounds a bit like seeing stars align.

Exactly.

Or finding your own personal Da Vinci code.

Yeah, if you read my memoir in a mirror backwards, you’ll actually get the Fibonacci sequence over and over again.

I’ll have to try that.

Ian laughs.

You know, I remember Doug Wilson talking about how an author wonders how many people will read their book… you know it could be millions, or just a handful—and not counting the author, every book has at least one reader… but how incredible would it be to see Cove Mountain attract and touch a wider audience? I hope it does.

Yeah, me too. I appreciate that.

And here with Shelf of Crocodiles you’ve hit the big time.

Hey, it’s a real honor to be interviewed, Curtis.