On a jogging pass through the plays of Anton Chekhov, the doctor-writer who thrived in Moscow’s literary circle and became a patron saint of the theater world, a thread of dialogue stopped me in my tracks.

In Ivanov, a noisy, soapy tragedy written when a 27 year old Chekhov had yet to see his work onstage, we find the straight-shooting Doctor Lvov calling out the play’s title character—a depressed, debt-ridden landowner who bemoans his fate while making things worse.

Lvov nails Ivanov for neglecting his sick and dying wife… and for planning to marry his best friend’s twenty-something daughter as soon as he’s in the clear. What follows is a near homily, a short, secular faith appeal that’s as shrill and preachy, (if not less operatic) than your old-school Televangelist.

With Ivanov snarling back, Saint Chekhov takes the pulpit:

IVANOV:

“Think a little, my clever friend. You think I’m an open book, don’t you? I married Anna for her fortune. I didn’t get it, and having slipped up then, I’m now getting rid of her so I can marry someone else and get her money. Right? How simple and straightforward. Man’s such a simple, uncomplicated mechanism.

No, Doctor, we all have too many wheels, screws and valves to judge each other on first impressions or one or two pointers. I don’t understand you, you don’t understand me, and we don’t understand ourselves. A man can be a very good doctor without having any idea what people are really like. So don’t be too cocksure, but try and see what I mean… “

LVOV:

“You can’t really think you’re too hard to see through, or that I’m too feeble-minded to tell good from evil.”

-Act Three1

As anyone who’s raised or (as I have) taught teenagers knows, Ivanov’s rant is a dodge. It’s something that any cornered person trying to get out of trouble might scrape together, especially when he’s obviously taking the ‘simple and straightforward’ actions he sneers at. Judging by action, Lvov’s right—Ivanov is getting rid of his wife sick with Anna by doing nothing, and cavorting with a young, rich plaything who wants to marry him. Of course, to Ivanov (and in his shoes, having been called out so bluntly, who wouldn’t equivocate and appeal to complex motives), the Doctor’s words are nails on the chalkboard.

Thinking of Chekhov’s canon, his recurring themes and messages, and the nascent secular humanist gospel that was spreading its wings among his contemporaries, the monologue pops with meaning.

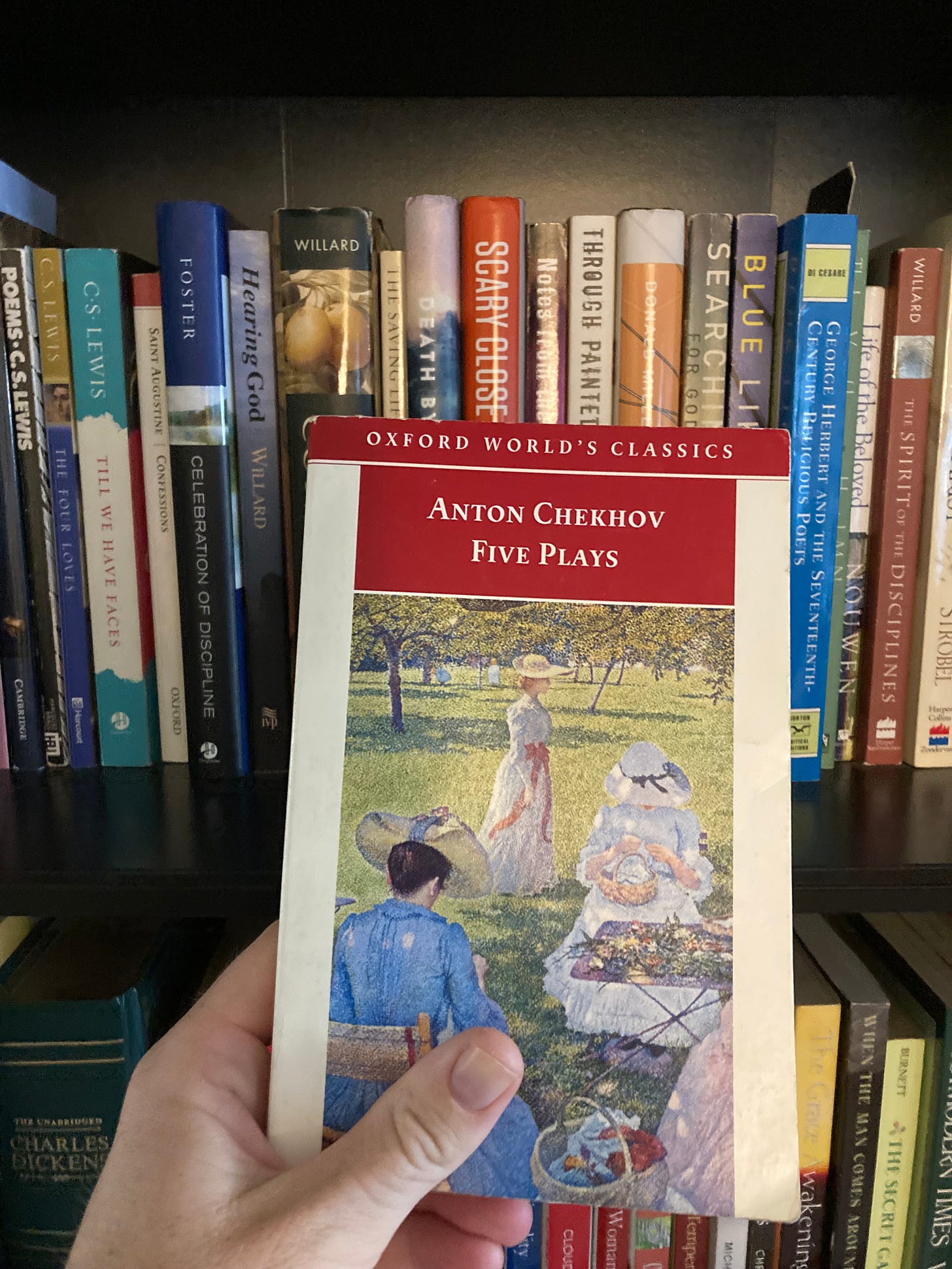

In his introduction to Five Plays, biographer Ronald Higley cites Chekhov’s own writing as evidence that the goal was reverse-engineering our notions of moral judgment.

That is, tortured souls like Ivanov are the hero.

Moralizing prigs like Dr. Lvov? The villain.

On second glance, and considering the timing—the play hit theaters only two decades before an atheistic, murderous alternative showed Russia’s Orthodox Christianity how to make hard judgements—the hero’s self-pitying words are all the more naïve.

But they light up a tenet of secular humanism: individual thought, reasoning, desire, and personal inclination are, with the exception of those unenlightened chumps who won’t vote the right way, divine and unassailable.

Chekhov’s dictum runs something like:

God, Bible, Church, family, society…. hypocritical through and through.

Humans don’t understand themselves, let alone each other.

All is relative.

Therefore, no judgments and no moralizing.

If this sounds familiar—and in the age of pride flags and atoning for one’s whiteness, all too one-sided—it’s a sober history lesson. A reminder that our culture’s casual secular assumptions started with their own prophets, apostles, and for lack of a better analogy, their own Sermons on the Mount.

On a side note that’s not unrelated, the naturalistic assumptions that were all the rage in Chekhov’s day makes their own leaps of faith.

In a Godless universe of crashing atoms and total nothingness, reason exists.

Even more miraculous, individual consciousness brims with meaning.

A Doctor’s Scrutiny

Of course, Ivanov’s plea has its half-truths.

But despite being true in a deeper sense—for who knows a person's thoughts except the spirit of that person, which is in him?2 —and fair enough on the surface, where passing impressions only skim the water, the claims crumble when put to the test.

For starters, and while he drove the message home with impressive literary output, Saint Chekhov contradicts himself.

No judgments, ever.

With the sole exception of this judgment I’m making right here, right now… except Ivanov’s judgment on this prig of a Doctor.

Second, Ivanov’s insistence that he shouldn’t be judged for his clear, selfish motives is the stuff of eight year-olds. If you read or watch the play, he does exactly what the Doctor accuses him of. For three out of four acts, Ivanov broods to anyone who will listen. He ignores his sick wife, making excuses when the Doctor urges him to sell everything and take her to a warmer climate before she dies of tuberculosis. He self-medicates by partying, asking people for money, and wailing about his past. When the flirty, underage, and well-heeled Sasha throws herself at him, he raises no fisticuffs.

In short, he’s a jellyfish… the first of a whole smack of moody, misunderstood, drifters beached all over the Chekhov canon. When called out directly, he lashes out because he knows it.

It’s a more a case study of something Chekhov would probably not admit, though no doubt understood. Next to actions, eloquent rationalization dwindles to minutia. As the pagan Aristotle noted, characters, (onstage or off, and even in complex, contradictory ways) define themselves through repeated action.

With that in mind, the Doctor’s gruff insistence on sober judgments involving good, evil, and a fair assessment of someone’s actions, is no snobbery. Unpleasant, and at the worst, impolite? Sure.

But it’s what responsible adults do every day.

Form, Heart, Content

To give credit where it’s roundly due, the scene’s cut from a fine texture.

Where European theater in the 1880’s loved caricature, eye candy, and predictable, crowd pleasing plot templates, Chekhov gave complexity. Like his characters, including one Uncle Vanya, who fires a gun at his hated brother-in-law and misses, twice, Chekhov zigs where he ought to zag.

Awkwardly funny one moment and then melancholic the next, his plays find the unexpected pathos in daily interaction—while filling the stage with memorable characters from every layer of old Russia’s social strata. Watch a play like The Cherry Orchard and you’ll notice the subtle, surprising moments that laid groundwork for drama schools, film acting, and the realism of modern drama.

But—and in a refrain you’ll see more than once if you read Shelf of Crocodiles— admiring craft doesn’t mean giving a pass on the crafter’s big ideas.

Fast forward through Russian communism and the sixties. As we saw around us in the summer of 2020, (to name one example) abolishing judgments and flipping over moral boundaries for the sheer thrill of it is a one way road to a burning police precinct.

Even if it takes weeks, a decade, or a century and a half to get there.

I mention a century and a half because that’s how long ago Chekhov, with his contemporary Henrik Ibsen, thrust postmodern notions into the public arena, the imagination of Europe’s culture elites… and through them, the art, literature, and educational institutions that would influence a billion people, on both side of the Atlantic, and in many other places.

Ideas like no absolutes, you can’t judge me, and I’m doing what’s true for me are less hip and new agey than we think. A hundred and fifty years ago, and to add on to a line by Theodore Dalrymple, Ibsen and Chekhov, two rogue playwrights not even writing in English, got there first.

Still, and if we pan out a little, even Chekhov’s priggish Doctor and misunderstood bad boy take up twisted, if archetypal roles in the Christian story. To put it crudely, Ivanov’s the martyr, the suffering victim who, for all his flaws, dies on the cross (the cross being Chekhov’s gun, as it were) of black-and-white, unflinching moral judgment.

Lvov, and every one of his moralizing ilk, are the crucifiers, the bloodthirsty crowd calling out for crucifixion. If dramatized moral showdowns grab our attention, as the notoriously chaotic first staging of Ivanov did when audiences first watched it, we should remember that all substitutes take their cue from the real thing.

And by the real thing, I mean something that the well read and classics-minded are starting to call Christian Humanism—the recognition that freedom, moral judgment, rational inquiry, and the individual’s dignity, all find their origin in a death and resurrection two thousand years ago, a life riven with miracles in flesh and physical time.

While it’s worth exploring in a dozen more essays, (and if you’ve got a lock on something I should read, drop a comment and tell me), the Christian Humanist stands where the all-too-real Ivanovs tend crumble.

He stands because unlike Ivanov, the burden of final, totalizing judgment—the test of worthiness that, for all our Tik Toking, stoic accomplishment, and personal cheerleading squads, we’ll never, ever pass—rests somewhere else.

On someone else’s shoulders.

Endgame

It’s unfortunate that so much superb, and thoroughly modern stage drama is no blueprint for spiritual life. As Ivanov shows us in spite of itself, modern drama isn’t even a recipe for daily life.

Unlike monotheistic religions, and the Christian Gospels in particular, there’s little in Chekhov to bring out our potential, give us rest or joy in suffering, and nudge us to elevate others when we’d rather be looking at our phones.

If moral judgments are the price of admission, then the endgame is avoiding a fate like Ivanov’s, whose aversion to judgment leads him to a place where he can’t escape the ones pounding his own head.

In Act Four, and with the Doctor confronting him in the middle of his wedding to wife number two, a broken, and almost giddy Ivanov spies his way out.

IVANOV:

“... I’ll put an end to all this here and now. I feel like a young man again, it’s my old self that’s speaking.

[He takes out a revolver]

I’ve rolled downhill long enough, it’s time to call a halt. I’ve outstayed my welcome. Go away. Thank you, Sasha.”

-Act Four3

He walks offstage, and in the sad, prophetic words of David Foster Wallace, he kills the tyrant—the one with little mercy, a complete record of his life and shortcomings, and permanent residency inside his head.

In truth, is any pesky tormentor harsher than our own internal tyrant?

While Chekhov intends him as a martyr, (in a breathy exoneration, Ivanov’s young bride Sasha defends him to the end), Ivanov foreshadows much more than the playwright intended.

Remembering that plays, novels, and scientific theories laced with secular faith danced before the horrors of the gulag, the blitz, and the concentration camp like so many pied pipers, the words of Czech playwright Vaclav Havel come to mind:

“As soon as man began considering himself the source of the highest meaning in the world and the measure of everything, the world began to lose its human dimension, and man began to lose control of it.”

As the mid Twentieth Century showed us, if we proclaim total liberation from God, good and evil, and moral judgments, we’re in for a quick and bumpy ride over the abyss.

It’s a final irony that Anton Chekhov, every bit the probing, moralizing doctor he castigates—to his credit, he really was a doctor before becoming a writer—misdiagnosed the problem. Where he mounts his own pulpit and waves human reason, permissive compassion, and emotional complexity around like a battle flag, Jesus of Nazareth, the one who raised the dead and knew what was in a man, took the physician’s job seriously.

In the kindest pardon a judge could ever give, He paid the penalty himself… and silenced our own tyrants once and for all.

In medical terms, He cured the cancer.

As for all those wheels, valves, and tiny screws inside of us… it’s more complex that you ever imagined. To the one who knows how, you might say that’s a lot more tinkering to be done.

Anton Chekhov, Five Plays. Oxford, page 44.

First Corinthians, 2: 10 -12, English Standard Version

Anton Chekhov, Five Plays. Oxford, page 50.

Excellent and thought-provoking, as usual! Thank you, C.M.!

SOLID article. I love the topic.