Ireland, Venus, Odds and Ends

Thoughts on ‘The Banshees of Insherin’ and ‘Perelandra’

Well, crocodiles… here we are.

Before Thanksgiving, I went and did something I do twice a year, if that.

I went to a picture show—one at Sacramento’s hip, art-deco Tower Theater, where The Banshees of Insherin, the latest flick by perversely funny filmmaker Martin McDonagh (same one of In Bruges, Seven Psychopaths, and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri) was playing.

Odd critic that I am, and after stumbling across a startling review of ‘Banshees’ by one Grayson Quay —one that interprets the movie’s simple plot as a struggle between traditional values and the ‘pure expressive individualism,’ of gender studies and twerking Tik Tok channels—I couldn’t resist chiming in.

If that sounds like a lot, please bear with me.

And if you’d rather scroll down to D.T. Adams’ delightful column on ‘Perelandra’ the second novel of the Lewis Ransom Trilogy, no hard feelings.

The Banshees of Insherin

Onstage or onscreen, Martin McDonagh’s an acquired taste.

For the discerning viewer, his unshy violence, coarseness, and casual gallows humor leaves quite the bitter taste. But like screenwriters-director Kenneth Longerman, Aaron Sorkin, John Patrick Shanley, (and of course… patron saint David Mamet), McDonagh piques my interest because he was a playwright first.

As an old showbiz saying goes, movies make you famous, T.V. makes you rich… but theater makes you good.

When you’ve got a shoestring budget, no special effects, and the task of keeping an antsy, highly perceptive audience in their physical seats for one line of dialogue after another, you learn to do an awful lot with whatever you have.

To that end, it’s a treat watching McDonagh dial back the fight scenes and flashbacks of his previous movies and run wild with Irish brogue—a reedy, pattering dialect that swings gracefully from banter to menace. True to the stage and with a dialed in cast, he reminds us that a word, a phrase, or even a pause can go nuclear.

The hardscrabble playwright also shows up in a whittled down conflict.

Like the trailer suggests, ‘Banshees’ follows two lifelong friends (Brendan Gleeson and Colin Farrell respectively, or as Roger Ebert recently coined them, a reincarnation of Laurel and Hardy) going through a total and painful breakup. Set on a remote island of forty inhabitants —one where even the bored, horny teenager Dominic knows everyone’s dirt—the breakup is hopelessly public.

With explosions of the Irish Civil War pattering just across the water (though the moodiness feels perfectly modern we’re in the early 1920’s), the tragedy begins when semi-retired Colm (Gleeson) suddenly announces he doesn’t want to talk to the good-natured, uncultured Pádraic anymore.

Pádraic’s crushed—and in Colin Farrell’s hands, sincerely so. He’s reduced to a shadow whose only company is the donkey who helps him deliver milk.

Colm’s reason for breaking up with him?

The guy’s dull and he can’t stand him.

With the time he has left, Colm would rather write folk songs in peace and quiet—and with any luck, leave a tune for posterity. When the local priest, and Pádraic’s no-nonsense sister Siobhan, (one Kerry Condon, acting with own native tongue) both argue that refusing to talk to someone simply isn’t nice, Colm has a reply.

Nobody remembers ‘nice’ people.

But they might remember someone’s music—after all, they remember Mozart.

“Well I don’t,” a drunken Pádraic snaps, “so there goes that theory.”

When Pádraic won’t stop bothering him, Colm makes a promise:

COLM: “What I’ve decided to do is this. If you don’t stop talking to me, and if you don’t stop bothering me, I have a set of shears at home, and each time you bother me this day on, I’ll take those shears, and I’ll take one of me fingers off with them, and I’ll give that finger to you, until I have no fingers left. Does this make things clearer to you?”

PADRAIC: “Not really, no.”

Here, the dreary atmosphere of pubs, coastline, and gloomy weather starts to crackle.

Is Colm bluffing, the horny teenager wonders out loud.

And here Grayson Quay dives headfirst into the irony—irony that starts, but in his mind, does not end with a fiddle player cutting off his own fingers for peace and quiet. Where Quay sees philosophical satire that McDonagh probably didn’t intend, he raises our eyebrows:

“Colm’s philosophy is pure, expressive individualism,” Quay writes. “It’s the “modern self” whose rise and triumph Carl Trueman so skillfully traced. Such people see their lives as blank canvases rather than as thin threads connecting their ancestors to their descendants.

That modern self, of course, has nothing to do with one’s family or neighbors or unchosen obligations… Colm has to withdraw to pursue his art because, for him, community and creativity are opposing forces.

The traditionalist’s response to the expressive individualist is predictable: “No. Stop. Don’t reject the ties that bind us. Pursue self-actualization if you wish; only let us remain friends while you do so.”

To the transgressive, these terms are unacceptable. Any restraint on total self-creation is violence, even if that violence is, in practice, self-inflicted.”

It sure blows the eyelids back.

But if the hip, rich, wine and beer drinking audience at the Tower Theater is any measuring stick, it’s probably an interpretation McDonagh’s fanbase needs to hear.

Like a running back on a breakaway, Quay sprints and sprints:

“Colm’s spiritual descendants in the 21st century claim to be crippled by the oppressive isms and phobias of the ‘cishet’ white patriarchy. They list six mental illnesses in their Twitter bios. They pursue risky sexual encounters, zonk out on SSRIs, and disfigure their bodies with facial piercings and double mastectomies. They even threaten suicide… In each case, they refuse to believe that they’re hurting themselves. They insist that the solution to their anguish is always more transgression. The more they pursue freedom, the less free they become.”

That’s quite a claim.

But scroll any thread or news headline, and you might not be surprised. And if you take Colm and Pádraic’s conflict in insolation from the rest of the movie (as Quay does), sure—maybe it’s not a bad parable for the proud, self-centered individualism that insists all hard realities (with them families, biology, co-workers, and especially bathrooms) bend to its whim like a spoon in the Matrix.

But if Quay nears the end zone, he doesn’t quite cross it.

“Even as Pádraic swears eternal enmity, Colm thanks his erstwhile friend for watching his dog after burning down his house. “Any time,” Pádraic responds. Thank God. If we manage to extinguish all love for our neighbors, we’re truly damned. As the credits roll on McDonagh’s film, grace still has some room to maneuver.”

What room would that be?

Without giving away the details that lend a particularly Irish tragic bleakness to McDonagh’s tragic ending, I have to disagree.

In fact, the scene from In Bruges, when a wounded Gleeson defenestrates himself from a tower to warn Farrell that an assassin’s coming for him, gives us a much more of what Quay’s hoping for—a glimpse of grace drenched in sacrifice…right before some hard-to-miss symbolism of purgatory.

But with Colm’s house burnt down, civil war guns booming over the ocean.and Pádraic alienated and alone, Banshees ends on the grim, cosmic note.

In short, not even close.

Where Quay casts McDonagh is a kind of Flannery O’Connor, he’s a lot closer to stage legends Harold Pinter and Samuel Beckett—and all the grace of Waiting for Godot.

Still, and even if he misfires, Quay sees something in bleak, 21st century tragicomedy that the non-Christian audience really fecking should:

“For McDonagh, the purpose of the conflict between the Pádraics and the Colms of the world is not the victory of one side or the other. It’s the revelation, however fleeting, of the One who reconciles their warring impulses. The One Who is both Judge and Outlaw, Monarch and Revolutionary, Center and Margin, Alpha and Omega.”

Not dull by any stretch.

Some Dialogue for the road

Dominic, to Pádraic: “Why does he not want to be friends with you no more? What is he, twelve?

Siobhan, to Colm: “What the hell’s going on with you and me feckin’ brother?”

Colm: “He’s dull, Siobhan.”

A pause.

Siobhan: “Well he’s always been dull.”

Dominic: “Would you not want him to have to do the one finger, to see if he was bluffing like?”

Siobhan: “No. We wouldn’t.”

Dominic: “Because worse comes to worst, he can still play the fiddle with four fingers, I bet you.”

Authors to Read

‘Perelandra’ Mixes Symbolism and Suspense

by D.T. Adams

If we traveled by coffin to a second, nascent Eden, should we be surprised to find another Eve being tempted by a serpent?

Maybe not.

But with the skillful pen and cosmic imagination of C.S. Lewis, we are. In his case, surprise is usually an understatement.

Last time, I introduced the Ransom Trilogy, Lewis’s science fiction series following Dr. Ransom and his interplanetary adventures. This time, I’d like to take a closer look at the second novel in that series: Perelandra.

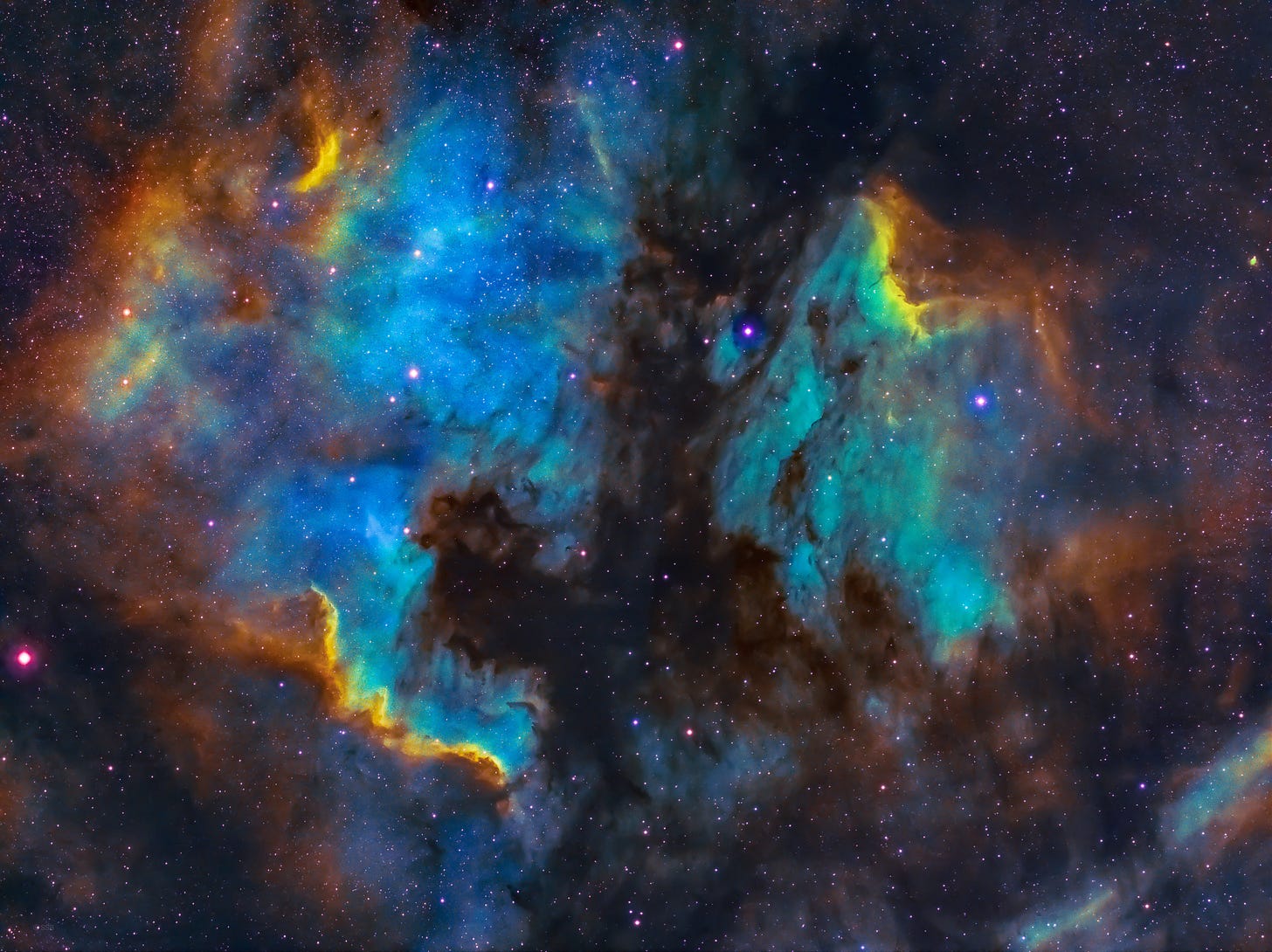

In this novel, Ransom travels to Venus, or Perelandra. He’s called there by the Oyarsa of Mars, who provides him with a coffin-like box perfect for space travel. Upon arrival, he discovers an idyllic world—islands inhabited by strange creatures, and wonderfully satisfying fruit trees that float and move with the waves of a golden ocean.

Soon, he encounters a woman-like creature.

While not human, she resembles humanity and is searching for her husband; they’re a sort of Adam and Eve on this planet. Shortly after Ransom arrives, he realizes that he’s there to prevent the corruption of this virgin world by Weston, a colleague-turned adversary from ‘Out of the Silent Planet’ who traveled there in his own spaceship and is a servant of the twisted Oyarsa of Earth. The temptation of this second Eve takes up a large part of the book, wherein Weston—demon possessed and not shy of a good Exorcist impression—tries to convince her that the commands of God (Maleldil) are meant to be broken.

With the whole world and its future generations hanging in the balance, Ransom tries to keep her from disobedience. In a thrilling, and finely calibrated interior monologue, he fights through his own doubts and timidity, resolving to stop Weston with fists and teeth…even if he goes down with him.

In the fray, Ransom’s heel is cut, a wound that stays with him for the remainder of the series. However in a moment of near symbolism that’s resonant enough, he crushes Weston’s ribs.

“I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and her offspring; he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel.”

- Genesis 3:151

Add to this that Ransom’s name is, well, Ransom; his final victory over Weston comes in a fight in a cave underground; he spends several days underground before emerging…and you get the idea.

He’s a humble philologist turned Christ figure, a role that carries him into ‘That Hideous Strength,’ the final novel of the trilogy.

There’s much, much more imagination, story arc, and symbolism to mine…and we’ll no doubt sample when I come back with my thoughts on ‘That Hideous Strength’ to round out the series.

If you haven’t read Perelandra, it’s time you do.

If you’ve read it already, maybe it’s time you revisit the story with Lewis’s lucid picture of this ultimate conflict and victory in mind.

Word on the Pond

On that interstellar note, just a reminder:

Stay tuned for a soon-ish interview with Christiana Hale, author of ‘Deeper Heaven: A Reader’s Guide to the Ransom Trilogy’, here on Shelf of Crocodiles.

Until next time.