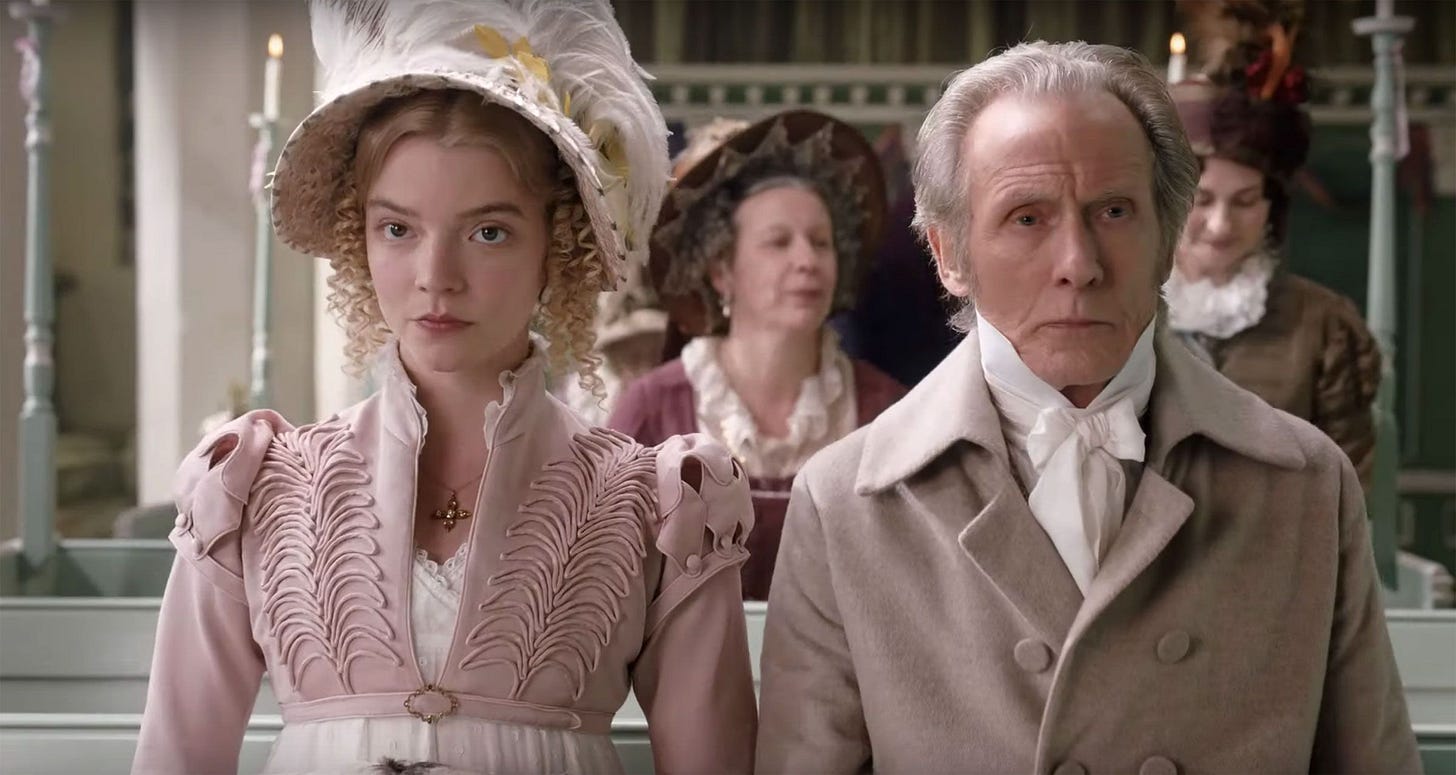

In 2020, yet another film adaptation of Jane Austen’s novel Emma hit theaters. That her books (even without the added zombies) are still bestsellers, and still regularly made into movies, begs an obvious question: why are novels where the only action scenes amount to one character taking “a brisk walk out of doors,” still so popular?

While her stories are elegant, conversation heavy, and deceptively simple, their impact doesn’t lie in the fact that romance and marriage are recurring topics. Many adaptations belie the fact that, even with our present case of ‘Jane Mania’, we still don’t get her.

Secret Sauce

Austen captures all of us because she pins down human nature.

Her arrow hits the mark with such devastating accuracy that we still feel it, even when it takes some time to understand what it is that stings.

As it turns out, ‘Emma,’ was the last novel Austen published during her lifetime. Subtle and masterful, the first chapter kicks off with a portrait of complete and total self-assurance.

“Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.”1

Reading on, we learn that Emma’s the youngest of two daughters, and that having been raised without her mother but with a ‘most affectionate’ and ‘indulgent’ father, she’s been mistress of the house from a young age.

But one detail explains her soaring confidence—Emma’s friend and former governess, Miss Taylor, has just married one Mr. Weston, who Emma introduced to her. Naturally, Emma takes full credit as the ‘matchmaker,’ and immediately sets her sights on setting up another couple.

Austen herself noted that Emma is a character who “no one but myself will much like.” Blessed with beauty, wealth, and a father who sees no fault in her, she’s the Queen Bee of her social circles. Everyone—with the exception of straight talking family-friend Mr. Knightly—gives way to her. Spurred on by this halo-effect, Emma thinks she’s great. Special.

Furthermore, she thinks she can read people down to the marrow, even to the point of knowing what others are thinking and feeling. To that end, the stories she tells herself as the ‘town matchmaker’ become something like the Secret Knowledge; truth that she alone can decipher and disseminate.

Lively and sharp, she’s nonetheless a character best described by American Idol Judge Simon Cowell: “You’re not as good as you think you are.”

Who Likes Who?

Early in the story, Emma befriends the good-natured, pliable Harriet Smith. Thinking she’ll improve Harriet’s low standing and desirability through disciplined studies, Emma decides that it’s much more pleasant to chat with her and let her imagination roam. For Austen this is dangerous territory: imagination divorced from “industry, patience and judgment” quickly turns dangerous.

Emma goes to work matching Harriet with Mr. Elton, the vicar, as she sees plenty of “clues” that he’s partial to Harriet.

Meanwhile, during a dinner party, a piano arrives for a young lady named Miss Fairfax; a gift from a mysterious benefactor. Rushing in like detectives, Emma and her friend Mrs. Weston launch theories of their own, arguing with a set of ‘proofs’ to flesh out their own foregone conclusions.

Of course, and like two Portland moms screeching about how many masks to wear at yoga class, they’re both wrong. But in the moment, and like so many of us, they’re convinced that they’re right.

When an annoyed Emma snaps: “How you take up a notion and run away with it!” it’s Jane Austen winking at the reader.

But if we’re in on the joke, the at the same time, the joke’s on us. Austen wants us to see that, like Emma, we do this all the time. We’re prone to seeing the world through our own narrative—one often soaked in pride or vanity. We grab hold of appealing narratives with a vice-like grip and then bend all the facts to justify it.

In other words, our thinking and reasoning is deeply connected to our hearts.

Narratives Aren’t Neutral

Austen makes this point when Emma tries to set Harriet up with Mr. Elton. She notes hard evidence—when Mr. Elton comes over to watch her paint Harriet’s portrait, he lathers praise and gushes over her other drawings. He’s deeply concerned when he hears about Harriet’s sore throat. Considering herself a keen observer of overwhelming facts, Emma doubles down. She even convinces Harriet to refuse a marriage proposal from a poor, but respectable young farmer.

But the trap springs in a carriage ride, when Mr. Elton proposes to Emma instead.

Emma’s flabbergasted. What about Harriet?

Realizing Mr. Elton was only, and on second glance not really feigning interest in Harriet to get closer to her and her 30,000 pound dowry (when Emma refuses, he goes off and settles for someone with 10,000 pounds instead), Emma grimaces. But she doesn’t learn that every “fact” is open to a double interpretation.

“Everything we hear is an opinion, not a fact. Everything we see is a perspective, not the truth.”

-Marcus Aurelias

It’s a lesson that grows more important every year, especially in the quote-unquote ‘information age.’ But even that label is an extreme misnomer. It suggests we’re all swimming in a pool of random facts, as if life can be summed up by a lot of disparate, disinterested statistics.

But knowledge, like narrative, is never neutral.

Rather than fact people, we’re still story people, and we’re deep in the grip of the ones we tell ourselves. Even the knowledge that seems neutral slips easily into our minds if it bolsters our own narratives.

The Tyranny of Preconceived Assumptions

Austen goes farther than this, showing us how, for the self-righteous anointed preconceived assumptions inflicted on others amount to a kind of noble tyranny.

She explores this truth with Emma’s father, who maintains strict dietary regulations. A leg of lamb should only ever be boiled; a basin of gruel should be always eaten right before bed; and for mercy’s sake, no one should ever eat cake.

If Mr. Woodhouse kept these standards to himself, he’d be a harmless eccentric. The problem is, he’s so convinced that his diet is the only way to live that he enforces his remedies on guests with a near-religious zeal. He can’t bear to see anyone expose themselves to the heresy of eating unboiled lamb.

“Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive… those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end, for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.”

-C.S. Lewis

Here again, Austen nails another pitfall of the human condition; and if it’s a bit cartoonish, don’t be distracted. In her eccentric characters, Austen’s shouting at us.

That his own guests might find his dietary guidelines odd or restrictive never crosses Mr. Woodhouse’s mind. To quote C.S. Lewis, when you’re looking through a window to a garden, you don’t even notice the window. Convinced we’re right and ever insistent when others object, we can “know something so well, we don’t even know it exists.”

Furthermore, in seeking to ardently close the minds of others, we’re at risk of sealing off our own in irreparable ways.

While preconceived assumptions are needed to make sense of the world and everything around us, the danger lies in our fully intact, ever-ready personal narratives closing in like some trick room in a haunted house. If we’re not careful, they will shut out minds and hearts, priming us to only see what we want to see.

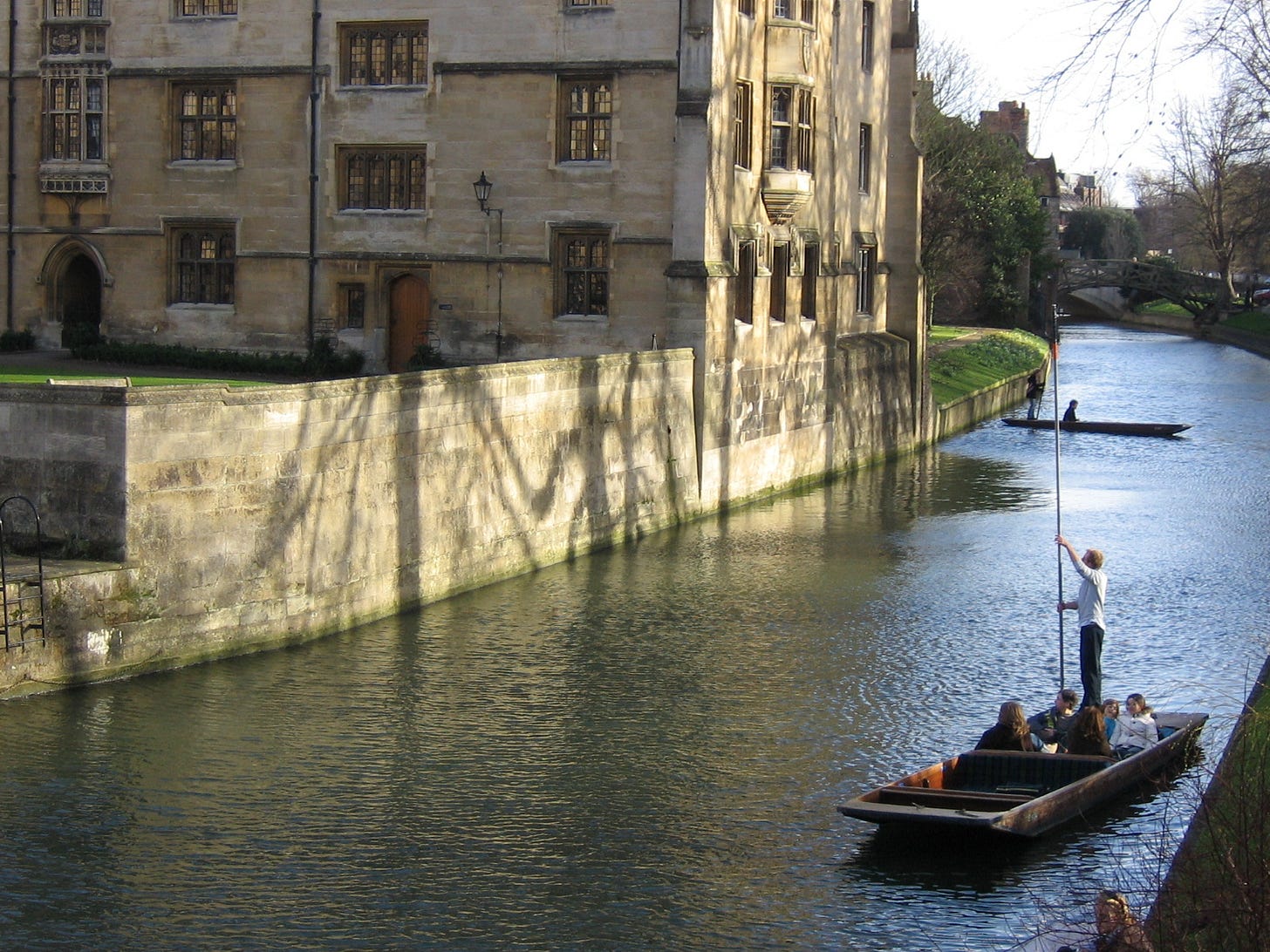

Badly Done, Emma

Near the end of the story, Emma visits Box Hill, a lookout point south of London with panoramic views. In all her years of living nearby she’s never visited, and that detail is no accident. Just as she sees the surrounding countryside for the first time, she gears up for a deeper perspective of herself as well.

In a culminating scene of her character arc, we see Emma at her very worst. At a picnic with her social group and in front of everyone, she shames Miss Bates, an older, impoverished, and chatty neighbor who thinks the world of her—and who Emma increasingly detests. The moment shows Emma giving vent to the petty, secret thoughts percolating in her heart, and it nails Austen’s premise that imagination with too free a reign flirts with madness, recklessness, and even cruelty.

When Frank Churchill starts telling jokes to liven the conversation, the talk dissolves into silliness. As Frank puts it, “any nonsense will serve.” When that moves into a proposed game of everyone saying either one clever or three dull things, Miss Bates good-naturedly says that she’ll have no problem finding three dull things to say.

Right on cue and before she even knows what she’s doing, Emma squashes her:

"Ah! ma'am, but there may be a difficulty…. you will be limited to only three.”

It takes a moment for Miss Bates to catch—and be grieved—by her meaning. Caught up in her own cleverness, Emma likewise misses what she’s done. But we don’t. In a flash we realize that she’s so indulged her thought life, grown so sure that she alone enjoys clear-sighted perception that any notion or how Miss Bates might feel after a barb at her expense never even crossed her mind.

Mr. Knightly—Emma’s one and only critic—privately and cuttingly rebukes her for her nasty behavior, “Badly done, Emma.”

The scene stings. It’s a swift backhand from Austen herself. It reminds us that for all the foolishness we see in other people, we have a difficult time seeing it in ourselves. In truth, it often takes something like this—a brisk, painful confrontation with reality that, if received graciously, lets some of our petty narratives die.

This, Austen reminds us, is often the beginning of real wisdom, and through tears of remorse on her ride home from Box Hill, Emma assembles it in jagged pieces:

“Every surprise brought humiliation. How to understand it, how to understand the deceptions she had been thus practicing on herself and living under. The blunders, the blindness of her own head and heart… She was wretched. To understand, thoroughly understand her own heart was the first endeavor. With insufferable vanity had she considered herself in the secret of everybody’s feelings. With unpardonable arrogance… she was proved to have been universally mistaken.”2

Real Wisdom Walked Around

What is real wisdom? The kind that, as Proverbs nine tells, begins and ends with the fear of God? What sets it apart from foolishness?

For starters, true wisdom flies in the face of what we want to believe.

Where it never flatters, and where it often means death to self, it does set us free. Austen demonstrates her mastery of the subject matter (human nature) by giving exactly what she needs. Today, Emma would probably be some high-flying influencer; and despite our culture’s insistence, she would not not need a Ted Talk on self-esteem, or more blarney about how special and unique she is. The blow to her pride is a saving one; and where an earlier Emma promised to change when she found herself mistaken, it simply did not work. At this turning point, there’s nothing driving her to just try harder and just be a good girl.

But neither is wisdom simply cold reason or logic; out on Box Hill, with ugliness and ignorance as plain as the sweeping view, the answer isn’t more intelligence, greater caution, or more sensitive social skills. We often feel we know what to do with goodness and truth. But real wisdom can only be seen when personified—when logic, clarity, and truthful thinking is wrapped in goodness, sacrifice, and finally, with love that really knows us.

In a plot that ends as gracefully as it lifts off, Mr. Knightly embodies this love for Emma, the kind that calls her out because it wants her very, and ultimate best.

Mr. Knightly isn’t blind to Emma’s faults—he does not flatter her, and he’s one from whom she’s “heard nothing but the truth.” Ever loyal, Mr. Knightley’s words slice through the muddle of her vain imaginings, and yet he loves Emma in spite of her faults. In the words of Austen scholar Stuart M. Tave, Knightley loves her with “a clarity of head and heart that allows neither to falsify the other.”

Real wisdom is never limited either to the mind or the emotions. In practice, it’s a radical change of the entire person, both head, heart and appetites, and with truth, goodness and beauty folded inside of that.

Where Austen leaves off, she points to the need for wisdom incarnate, for wisdom that lived among us and walked around in the person of Christ, both man and God who sees us to the dregs, and loves us still.

Austen, Jane. ‘Emma,’ Text citation from Project Gutenberg.org

Austen, Jane. ‘Emma,’ Text citation from Project Gutenberg.org

Nice! Indicting insight: “The moment shows Emma giving vent to the petty, secret thoughts percolating in her heart, and it nails Austen’s premise that imagination with too free a reign flirts with madness, recklessness, and even cruelty.”

Hey readers: if you love Noelle's essay as much as the crocodiles do, she's got another one all about Jane Austen on her own Substack 'Box Hill Talks.'

Check it out here: https://boxhilltalks.substack.com/p/judgers-haters-and-austen