Starting Off

It's high time I read 'Two Years Before the Mast.'

If you’re like me, your reading list is ten deep. While some titles, say War and Peace, might sit on the shelf like a fine wine, adding age and depth (and maybe self-delusion) to a collection before being corked open, others collect dust. I’m all for both, as my shelves abound with a growing stack of titles I haven’t gotten to yet. At the risk of sounding like someone who won’t admit they have a problem, I tell myself convincingly that I will, one day, read everything sitting there.

I know, I know, you’ve never heard that one before.

That day may never come, but I am working on it. A minute here, ten minutes there, an occasional audiobook and a handful of hard copies at a time.

If you’re new here, welcome!

If you’d like to support these occasional offbeat essays or simply share something you enjoyed here, don’t be shy—a like, a comment, a share, or an email forward goes a long way. Shelf of Crocodile is free, but you can also support it by upbraiding to a paid description.

Glad to have you here.

One title that I should have flipped open and finished long ago is Richard Henry Dana Jr.’s 1840 seafaring memoir ‘Two Years Before the Mast.’ A copy landed in my room when I was twelve or thirteen, along with a fact I now take much more seriously—I’m adopted, and through my birth mom’s family, Richard Henry Dana Jr. is a distant cousin, likely five times removed.

Through a generous openness on the part of my parents, I’ve gotten to known my birth mom (her name starts with ‘R’), her story and mine, and her family quite well. One tidbit of my adoption story is that when R, twenty years old, single, and away in college, decided that an abortion was the obvious solution to an unplanned pregnancy, an older brother (my uncle, whose name starts with ‘L’) calmly, purposefully, asked her to reconsider.

While this part of my story doesn’t connect to ‘Two Years Before the Mast’ per se, it’s long worth mentioning. It’s a testament to R, L, the adoptive parents who raised me and came to share me with them, and God’s masterful, undeniable architecture in using all of them, at providential moments, to answer prayer.

Knowing that my lineage through this story-behind-the-story runs all the way to a well-known author and lawyer, (RHD famously represented the U.S. Government before the Supreme Court in the Prize Cases that gave Lincoln the ability to blockade southern ports during the Civil War), I’m piqued to learn of more cameos down the line. One cameo—and the last personal story I’ll get into before the book itself—involves my uncle L paying homage to RHD at the statue of him in Dana Point, California, at another providential moment.

As it turns out, a marriage proposal.

As the story goes, my Uncle L (and his soon-to-be fiancee, also an ‘L’) walked out to the statue at the center of the canal entrance of Dana Cove and the harbor. There, Uncle L kissed his fingers and touched his mother’s name on the base of the statue—she was named on a plaque along with other descendants of RHD who lived in the region—and asked his girlfriend L to marry him.

In another moment God, and no doubt the bronze, nine-footed RHD with his shirt off and his memoir-journal in his right hand smiled upon, she said yes.

Another voyage, in a family of voyagers, set forth.

“If it shall interest the general reader, and call more attention to the welfare of seamen, or give any information as to their real condition, which may serve to raise them in the rank of beings, and to promote in any measure their religious and moral improvement, and diminish the hardships of their daily life, the end of its publication will be answered.”

-Richard Henry Dana Jr., preface to ‘Two Years…’

With a personal connection to RHD’s classic gnawing on me, and having come across this fine, shelf-worthy copy (at a second-hand bookstore in hellish downtown L.A. nonetheless) here’s some impressions of the first thousand words or so.

Having Read The First Two Chapters…

I love it.

That is, I love the voice and style.

I can tell from the get-go this is a fine American memoir and that I will enjoy it.

True to genre and almost a journalist, Dana paints his subject matter in clear, laconic, load-bearing prose. This matches his goal of depicting brig life from the marginalized, bottom-rung sailor’s point of view, with the wider mission of evoking sympathy for his hardship, and improving his moral, spiritual and legal lot, (Dana, who became a famous lawyer, states as much a brief preface).

From the first few paragraphs you can see Dana restraining himself and holding to this mission. His clear, brisk pictures read like he lifted them from an actual diary.

“The fourteenth of August was the day fixed upon for the sailing of the brig Pilgrim on her voyage from Boston round Cape Horn to the western coast of North America. As she was to get under weigh early in the afternoon, I made my appearance on board at twelve o'clock, in full sea-rig, and with my chest, containing an outfit for a two or three year voyage, which I had undertaken from a determination to cure, if possible, by an entire change of life, and by a long absence from books and study, a weakness of the eyes, which had obliged me to give up my pursuits, and which no medical aid seemed likely to cure.”1

Like the famous first pages of Melville’s Moby Dick, Dana includes an inner snapshot of the protagonist—himself. Dana, like Melville’s Ishmael, steps out on the Boston docks a novice, drawn to the sea by a powerful motive.

The brisk, well-paced telling of it reminds me of George Orwell’s ‘Down and Out in London and Paris.’ As descriptions that tend (in this time period) to draw an awful lot of attention to themselves, Dana’s is candid—refreshing if you’ve spent any time tackling older works.

When Dana sees veteran sailors and notes the difference between his appearance and theirs, embarrassment and vulnerability are frank enough:

“But it is impossible to deceive the practised eye in these matters; and while I supposed myself to be looking as salt as Neptune himself, I was, no doubt, known for a landsman by every one on board as soon as I hove in sight. A sailor has a peculiar cut to his clothes, and a way of wearing them which a green hand can never get.”2

Dana gets bonus points for introducing the slang he and other characters use throughout. ‘As salt as Neptune’ and ‘green hand’ roll out seamlessly, easy to grasp. After describing the clothes that mark him a beginner, Dana pivots to a telling, even beautiful description of the real thing:

“Beside the points in my dress which were out of the way, doubtless my complexion and hands were enough to distinguish me from the regular salt, who, with a sun-burnt cheek, wide step, and rolling gait, swings his bronzed and toughened hands athwart-ships, half open, as though just ready to grasp a rope.”3

Detail after detail deepens the subject, hinting at the months and years that molded hands and complexion—and with the same, steady frankness.

Now back up.

Compare Dana’s brisk, opening snapshots to some from Moby Dick, starting with Ishmael’s self-analysis:

“No, when I go to sea, I go as a simple sailor, right before the mast, plumb down into the forecastle, aloft there to the royal mast-head. True, they rather order me about some, and make me jump from spar to spar, like a grasshopper in a May meadow.”4

It’s rich, but less believable. Already, we’re headlong in verbiage: ‘forecastle,’ ‘royal mast-head,’ ‘spar to spar.’ While Dana familiarizes such terms piecemeal—and with a glossary at the back—Melville rolls around in them.

Next to Dana’s motives for taking to sea, Ishmael’s run pedantic.

“And at first, this sort of thing is unpleasant enough. It touches one’s sense of honor, particularly if you come of an old established family in the land, the Van Rensselaers, or Randolphs, or Hardicanutes. And more than all, if just previous to putting your hand into the tar-pot, you have been lording it as a country schoolmaster, making the tallest boys stand in awe of you. The transition is a keen one, I assure you, from a schoolmaster to a sailor, and requires a strong decoction of Seneca and the Stoics to enable you to grin and bear it. But even this wears off in time.”5

There’s no knocking Melville’s insight.

Young men challenge themselves and seek out ‘unpleasant enough’ for simple reasons—honor and the need to test themselves, for starters. But where Melville conducts grand, vibrating notes from the very start, Dana strums his tune without pretense.

Critics think Ernest Hemingway fashioned his short, paired down sentences based on telegram language. His lesson from working for Western Union? Every word costs something. In stating his purpose so plainly and shading rote detail with plain, candid insight, candid description, I sense that Dana understands the cost too.

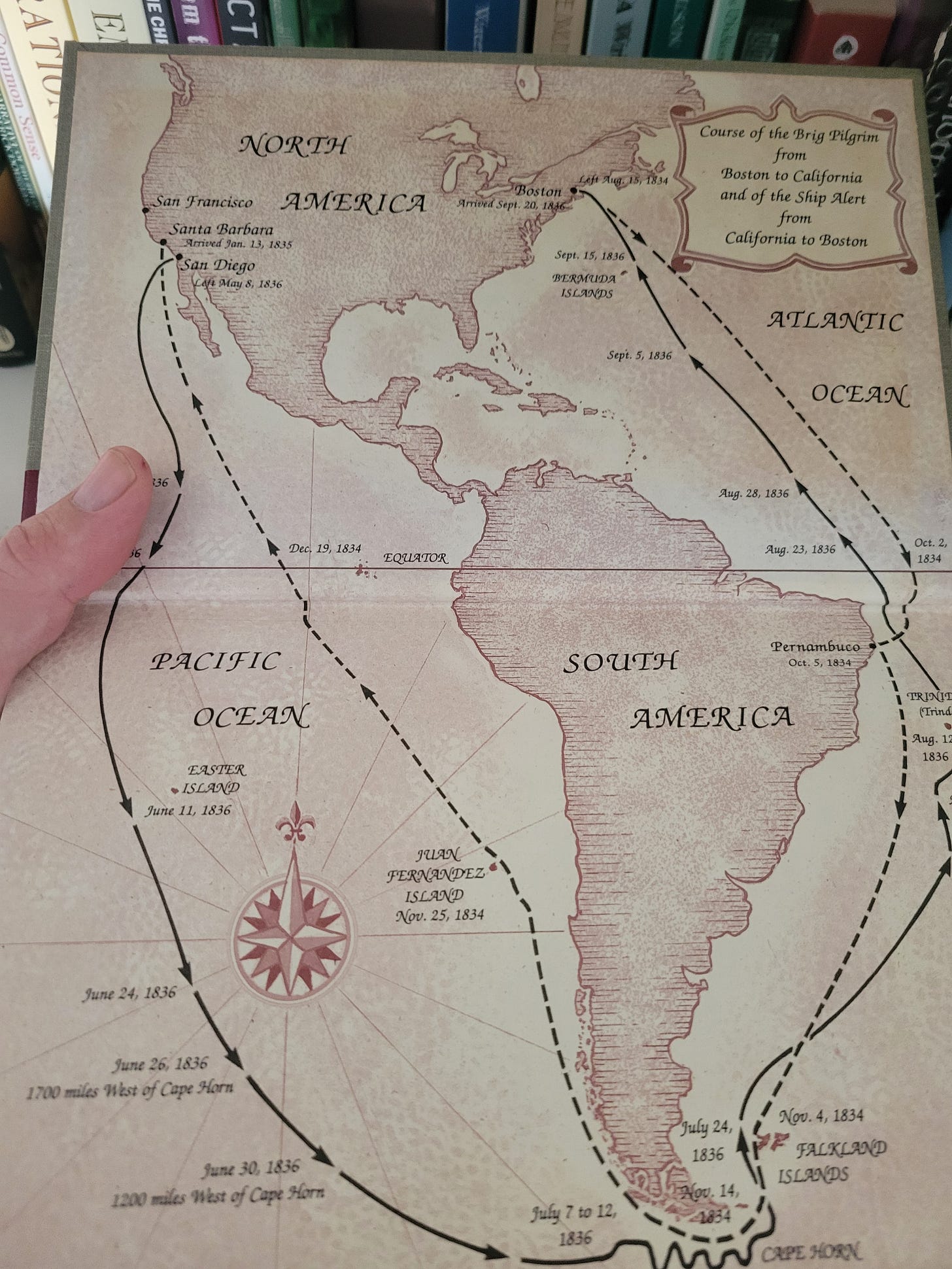

With prose matching his semi-journalistic aim, Dana confines his first chapter to a thousand words, if that—and then we’re off. When the Pilgrim sets off, it will sail down the Atlantic, around the tricky Cape of Good Hope, and up to California for a cargo of leather hides, and then all the way back again. Entry by entry, and with the necessary embellishment to put a torrent of raw, fresh, and no doubt overwhelming experiences into words, Dana our frank, uneasy narrator, brings us onboard.

“There is not so helpless and pitiable an object in the world as a landsman beginning a sailor’s life… the noise of the water thrown from the bows began to be heard, the vessel leaned over the damp night breeze, and rolled with the heavy ground swell, and we had actually begun our long, long journey.

This was literally bidding “good night” to my native land.”6

Will I Finally Finish Reading It?

I hope to.

Truth be told, I’m publishing this in the cracks of work, a daily commute, sons now one and three, and a middle-grade novel collaboration that I’ll be excited to share more about soon enough.

Life has grown busier since I hopped on Substack in the latter half of Covid Lockdowns in 2021—and it’s not just me. To the extent, and to be blunt, miracle that I’m still here on Substack (if only quarterly) I think of something a writing companion with twice the family size, a downtown pizzeria business, and some hefty MFA coursework yet to complete told me: responsibilities like kids and a family are indeed time-consuming, but they don’t leave with you no time to work on stuff.

Overtime, they become a kind of ballast, adding weight and stability as they shift the center of gravity. Kids, in other words, by forcing forcing limits on your time, rhythms, energy, and so forth, can make you productive overall. Choppy waters that would normally toss you every which way grow smoother as you hug the waterline, committed and on course.

Life doesn’t stop, as it were; the weight on your shoulders might grow heavier, but your focus narrows, priorities grow clearer—and if writing is a priority in the end, you’ll find yourself making time for it.

Kids are incredible, and cute, so there’s that.

If you’re thinking of having them, how’s that for wind in your sails?

As for reading through ‘Two Years on the Mast’ and honoring some of RHD’s living descendants, I’m working on that. Like my spread of books at any given time and oh, so many passion projects, I’m plodding through this one page by page and will be for some time. But having committed myself to said reading here, I might come back around with a full report once I pull into harbor. I get the feeling RHD would expect as much from a distant cousin, scribbling away on here.

*A note to myself: no pressure.

‘Two Years Before the Mast,’ chapter one.

‘Two Years Before the Mast,’ chapter one.

‘Two Years Before the Mast,’ chapter one.

‘Two Years Before the Mast,’ chapter one.

‘Moby Dick,’ chapter one.

‘Two Years Before the Mast,’ chapter one.

It's not every day that someone's TBR confessional includes such intriguing personal drama. Hearing about your lineage and how it contextualizes your reading of this particular book kept me reading through to the end! *grin*

*CORRECTION* ...and this might stir the pot a little.

I'm actually not RHD's great, great, Grandson -- more likely a third cousin, five times removed. Still a connection, but no direct link to a literary genius, haha.

Thank you to two readers in my family for catching that!