A little after Christmas, I caught up with author Kate Anger in her home town of Riverside. My wife and five-month-old son were there—nearly seven months later, that seems like ages ago—so it was quite the party.

At that time, Kate, a playwright, prose writer, and lecturer at the nearby University of California for seventeen years, had recently published her first novel—a crackling work of historical fiction called The Shinnery. As far as western drama goes, her novel couldn’t get more potent; it’s based on a true story that rocked her family, along with a small town in west Texas over a hundred years ago.

Ever the precocious critic, my five-month-old son made a suggestion: I should read Kate’s novel and then ask her for an interview.

The crocodiles conferred.

Kate generously agreed, and here we are.

Being familiar with her plays and how she taught playwriting (I’m not the only one who still remembers workshop day), I went in primed for straight drama. Having sampled Kate’s writing about place, family ties, and Southern California’s Inland Empire over the years, I was also curious how she’d depict life on the Texas frontier circa 1895. The answer, I found, was with riverine detail, gathered through research, travel, conversations with family and people in small towns, and many hours poring through old archives.

“I loved the research,” Kate said, “I could do it all day. And you should set everything in Texas because the resources are fantastic.”

Notes on the Interview

My talk with Kate covered a range of topics—family ties and family stories, the old west, survival, redemption, and making amends. We talked about how people of their time, and particularly those who came out west and struggled to survive in forgotten places deserve to have their stories told. Creatives that we are, Kate and I discussed writing, character development, and a few of ‘The Shinnery’s plot turns. If you’d rather read it first and avoid a spoiler, here’s your offramp.

“In 1895, my great-great grandfather shot a man dead on the streets of Rayner, Texas. Apparently, the man had ‘seduced’ and impregnated his daughter (my great-great aunt) and then forced her to work as a prostitute. My great-great grandfather stood trial for the killing and the region's papers enthusiastically reported on it… it was such a subject of shame in the family that my own grandmother, who lived to be 93, never knew of it. I became obsessed with the question of how it all went down, this seventeen-year-old girl from a loving farm family falling into prostitution. As I began writing, it quickly shifted from my great-great grandfather's story to his daughter's.”

-Kate Anger

I’ll briefly add that for all the research, and with the weight of a fully documented true story on its shoulders, ‘The Shinnery’ did not disappoint on the drama front. The novel follows Jessa—Kate’s great great Aunt, fictionalized—a sharp, tenderhearted seventeen year old living away from home for the first time. When Jessa gives her heart to the dashing, street-smart piano teacher named Will Keyes (the one with a sinister brother named Levi), what starts, in her mind, as a promising, if unofficial marriage morphs into disaster.

Knowing the true events—that Kate’s great, great Grandfather shot and killed a man for impregnating his daughter and then coercing her into prostitution—we can imagine the story arc. But as Kate reminds us, redemption rises from disaster.

Shouldering responsibility and the fallout from her mistake, Jessa’s determination to put things right echoes Antigone, Esther, or Ree Dolly from Winter’s Bone. That is, she blossoms—or as Kate puts it in the conclusive final chapters, she lays claim.

In short, and because Kate is such a treat for anyone who loves family, cherishes their faith, and itches for stories of the old west, I’ll end with this. For grown-up readers looking for unshy, character-driven fiction (there’s some harsh language and brief sexual content, but otherwise no asterisks), ‘The Shinnery’ is a sure bet.

Buy it, read it, and enjoy this interview.

‘The Shinnery’ with Kate Anger

C.M. You’ve written a rich piece of historical fiction based on your family. Where did this love affair with the family story begin?

K.A. Well, growing up we were very isolated. My mother’s family moved around—Texas, obviously, and then Blue River, Arizona, which was the most remote point in the continental United States, and they were cattle people. Then southeastern Colorado. My Mom went to the West Coast, my Aunt to the East Coast. My dad was from the East Coast and lived in California, he had no siblings…so we were isolated. And we would be at our Thanksgiving table, just the four of us with my little brother. I would watch the other families down the street pull up on the holidays with all these cousins… and I knew I had this family and we would see each other in summer, but it was so fractured. So looking at old pictures connected me to this larger family story because I felt kind of orphaned out here.

Did any books with strong family themes spur you along?

Well I love Little House on the Prairie books. In one of my reviews, it said ‘The Shinnery’ was like a Little House on the Prairie for grownups. And then there was a book called The Queen's Own Grove by Patricia Beatty. It’s fallen out of favor, but it was written about Riverside history at the turn of the century. I just loved this book and then you add the bonus that it's my place—it's Riverside, and it’s a local person who wrote it.

‘The Shinnery’ fictionalizes the events that led to a real murder trial.

Yes, it was my great, great Grandfather Reese Jones Fuston. I changed him to J.R. Campbell. But as you know, the novel centers on his daughter, my great, great Aunt who I named ‘Jessa’. She's the main character and it involves a trial for murder of her father. He—my great, great, Grandfather—shot and killed a man for impregnating and exploiting her. So that was the story I heard in very hushed tones.

I read that you first heard this story from cousins in Texas. Sounds like it wasn't something to bring up at the dinner table.

No… so I went to Texas. My Aunt was doing the genealogy, and this cousin that we met, he comes into the room, he pulls my Aunt aside, and he whispers this story about my great, great Grandfather. It struck me as so strange that it had been over a hundred years, and yet it was like a state secret. It was so fragile to him, this story and how we were going to feel about it and how we were going to judge the people involved. He made my Aunt promise not to write about it.

That’s telling.

My grandmother, who died at 93 years old, never knew this story. It was like a conspiracy of silence! Over the years, there was so much shame heaped upon it. So this cousin tells the story in this really shameful tone—and by the way, nobody asked me to not write about it.

We share a laugh.

Yeah, I feel okay. And he has passed, this cousin. I was a little worried about what his kids would think. They're, you know, my peers, my age, maybe a little older. But I met two of them in Texas and one in Oklahoma on the book tour, and they were thrilled that this bit of family history had been captured.

So before your novel, it was quite the secret.

Yes. So I have to confess even though it was harmful for people to hide, I mean, it's terrible, there's a little part of me that was very intrigued by it. I mean, a secret my grandmother never knew… and then came across this old photo, a photocopy of a photocopy, of a photocopy of the family. You know, my great, great Grandfather and his wife, and then the grown daughter with three or two other sisters—there were eleven total, but that’s too many characters to put in a novel—and front and center, is probably a three year old girl; the daughter she’d had out of wedlock. And my family was poor. We didn't do a lot of portraits. So the fact that they went and put this child front and center said a lot about those people to me. In spite of what they all went through, and in a shameful event, that little girl was not going to wear that curse. So I think the idea was trying to mix this aspect of the shame and the secret with the fact that the family didn't hide her.

You heard this story about twenty years ago. What was the timeline from hearing it to thinking, okay, there’s a novel in this, and from there to the actual writing?

Well…I started writing ‘The Shinnery’ in 2015. So yeah, a long time. I think that's hard for non-writers to imagine. It's like, how could you think about the same thing?

So the idea had time to percolate.

Well, what did I do in those ensuing years? I wrote plays. I started teaching playwriting. I always wanted to write a novel… and of course, no one knocks at your door and says, ‘Hey, I'm looking for a novel, you know, would you do that?’ I mean, nobody. So when the doors for writing for the stage opened, I went that direction, but I always knew I wanted to do it. And it's so hard… you know, there has to be this love of it, like something you have to do and explore. It's hard to do things when you don't see like, well, what's the result? I hope that I'll go faster with this second book I’m working on because I've learned some things, but you have to love parts of the process.

You wrote the ‘The Shinnery’ in third person, and with Jessa’s point of view. Was sticking with close, third-person the obvious choice?

Not at first, but eventually. When I started off, I thought it was the story of my great great Grandfather, like, I'm going to write his story and I'm going to do these different POVs. But it became her story really quickly. I think multiple POVs are wonderful. But for me and my first book, I wanted it fairly simple. So close third felt right—because you’re managing a lot of things if you haven't done it before.

It’s amazing how much you’ve done with that. Jessa’s thoughts build the setting, familiarize us with her life on the farm and her family. Then through her, we land in the uncertainty of a new arrangement, a house in town with rigid, unspoken rules.

That's what I wanted! I want us to be on her shoulder… and one of the questions that you asked, I thought it was interesting: ‘why have the killing, like the actual shooting, done off screen?’ It's like, by right, that could be some kind of climactic, dramatic moment. But you don't get to see it because she didn't witness it. And that was how it happened in real life. And I wrote scenes where she was there… but if you get the benefits of being in close third, then you also can't see things that she didn't see. So that moment before Papa goes to town and this thing happens, I tried to make that encounter dramatic and awesome. But the peak is when you know, she's leaving the barn after telling him what happened. When he yells ‘get out of the barn’ and she thinks she's been turned out from home...and then she learns that she's not being put out.

Yes. She thinks she’s disowned, but then he runs out and embraces her.

You can imagine a man at that time, the emotions he carries—and you know, he's always been the one in charge, the one taking care of things—and he's a wreck because he didn't protect her. In that moment in the barn, he just doesn't want her to witness his absolute meltdown… and that’s not how she understands it.

“He swung his arms and she flinched for a second before realizing that they were open to her, an invitation, an act of grace. Jessa threw herself into the embrace. They both wept, for all that was lost, and all that was held in this moment.

‘Why’d you leave?’ he asked, his breath warm in her ear.

‘You told me to go.’

‘From the barn,’ he said.

Jessa sobbed again, something like a laugh riding beside it. Stupid girl, she thought.

‘A man can’t hear news like that and take it in unless he’s got some time to himself. Couldn’t have you standin’ there watching me blubber. A man—a father—is supposed to know what to do.”1

Yeah, that scene moistens the eyes. Regarding Will’s death happening ‘offstage’ so to speak, there’s a vibe of Greek tragedy in that. Seeing the news wallop the characters is enough to get the job done.

What I’m always telling my playwriting students is: ‘you can set your scene in a battle, but you’re not getting a hundred bloody men and guns.’ Maybe the battle’s happening right over there and it’s this temporal state. Exposition is your friend, right?

Or if the action already happened, news of it’s trickling out.

And I try to do that. But I always try—and this is something just for, you know, writers—it's like, you can just have a character explain everything, but it would be very boring. You know, ‘this is what happened’…but if you look closely, there's always conflict and tension about it and you have to mine it. Is there conflict because there's other people in the room and they can't say what they want to say? You know, make the exposition as lively as possible.

I think that constant drip of tension makes those slower scenes pop. You have Jessa constantly navigating new terrains—first the Martin’s home, and then Will waltzing into her life, and then Will’s baggage with Levi. She’s constantly tiptoeing, figuring things out, taking risks. We could go back to that choice of sticking to a closed third point of view, but it really works.

I am glad to hear that. Yeah, that was really important to me, because you know, not everybody likes her. ‘Well, how could she be so stupid? How could she be so naïve?’ Completely invalid opinion, by the way.

Kate laughs.

No, it’s fine. All opinions are valid. But you have to think about the time period, right? I mean, women didn't know so much; they did not discuss things like the birds and the bees…she was on the farm, so her knowledge of procreation, all that was based on animals. Men and women and those kinds of relationships, her sisters always had crushes on various boys but it wasn't her thing. And so, I think the idea that she would suddenly be in this very different place and not by choice carries a lot of potential. I mean, the farm, being outside, helping her Dad with the animals, those places are where she felt competent. That's her landscape, right? And then she goes into this other place with all this coded language—people say one thing, but they actually mean another. And she’s a mother's helper, which she’s not particularly skilled at. So she's completely unprepared, and the head of the household, Mr. Martin, is not exactly a kind and patient man. She's stripped of everything. So when Will comes in (he’s the piano teacher) and he's kind to her…

Did Jessa surprise you as you wrote her?

Yes. There's even a part in the book where, you know, her heart is just smashed to bits. She's been, what do they say about horses? Rode hard and put away wet. She’s just devastated. I mean, she realizes that she proffered herself in love, that she was capable of such open, big risk taking love. And I think that's something I discovered about her. There were earlier drafts where she would like, ignore things, but that’s where it came to. She really believes Will, and even when things get slippery and she’s seeing things more clearly, that love and vulnerability doesn’t just turn on a dime. But by the time she really realizes what he’s doing, it's too late, and she’s pregnant. She turns pragmatic, very I know, but I have to get this name for my child. Through it all, she became more active.

What about the character based on your great great Grandfather? Any surprises there?

Well the issue was that some people didn’t like him. You know, ‘ the father is so horrible. He farmed her out, she was so wronged…’ I don't see it that way. Again, a man of his time, he made mistakes. But when you don't have any means of any money and something that you know, perhaps I could have put more in the book, there was a huge panic in 1893. Just like 2008, banks collapsed, people lost money, and then the banks couldn't loan. So it's just like, you're going to grow a bunch of cotton, and this is going to be your expected profit. You're going to borrow some money for your seed and your fertilizer and stuff. But with the bank collapse, there was no credit to be had, and he already owed this money. They were already living by the skin of their teeth…let’s admit that’s a weird phrase.

What about writing Will and Levi?

I think that there was a part of Will, who was as trapped as Jessa was, and a part of him that did love her and fantasize. I think a small part of him could see that, had their life been different... and it to me, it's in the scene where he remembers his own father, who was a farmer and sitting on his father's shoulders, Then, his backstory—his father died, his mother remarried a terrible man. His brother Levi rescued him, nursed him back to health from a near-death sickness. He’s indebted to his brother… but I think there are moments where he’s for real… because Jessa’s a great person and why wouldn't he love her? A little bit right? So I mean, I don't want to write just bad guys for the sake of bad guys. There’s not much redemption, but I tried to have aspects that weren’t like…and we kick puppies too.

Complex villains.

They probably would have been more complex, but it is a Western.

Kate laughs.

When they corner Jessa in that situation in the saloon, it’s a horrifying glimpse of what can happen.

And it’s a big topic today—sex trafficking of women. Yeah, so when I was constructing a plot, I had to deal with that. And, you know, a lot of readers were like, Oh, my God, this isn't really happening… and it really happened. My great, great Aunt was forced to work as a prostitute. Because they were going to tell her family and ruin her and she did not know what to do. That's reality, and that happens to young women all the time. So that part's not great. But again, that's the redemption journey. That's why we read, that's why we want to see human beings overcoming and you know, finding forgiveness and resurrection. Those are the themes, I think, in everything I've ever written.

What kind of source material were you working with?

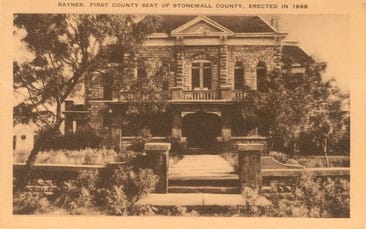

We had newspaper excerpts, some of which I include in the book. The state of Texas does an amazing job of having basically everything that exists from newspapers available on microfiche. You should set everything in Texas because the resources are fantastic. Even though Rayner, the town where the story is set and where she lives with the Martins, is now a ghost town, you can find online archives on it.

That’s great that they’ve preserved all that.

One more thing—I knew the courthouse was important, because that's what grabbed me. It was located in Rayner; it became the county seat. The scenes in the book where the arraignment happens are based on it. Okay… so my great great Grandfather helped build that thing. Turns out he cut those stones from the Brazos River and put them in place to build the courthouse. He was arraigned there after the shooting, and then years later, he was the sitting judge.

That’s fascinating.

I love that! It's just such a Texas story. Right? Life was different. You build the courthouse, you have your trial there…and later on, you are appointed judge.

Did the plot more or less present itself from the research?

So I am not a plotter. I'm a reverse outliner. With each chapter of the book, I say, ‘What did the characters want in the beginning of the chapter?’ And then I say ‘did they get it? Yes or no? And how are they different?’ I wish I was a different kind of plotter.

I want to ask about the last chapter, especially that last image with Jessa and Nellie riding off in the buggy together. Jessa’s had her baby, there’s a hint she’s getting married; Nellie is heading out to California to be a teacher. It’s a great moment and those last sentences are worth reading out loud.

I love those sentences. As a writer, to love some of your sentences and love some of your writing, I mean, it’s… because I don't love every word.

Well, I think this wraps a lot of the book together.

“Jessa felt like they were all new creatures, not their father’s daughters, but grown women unto themselves. Women driving West, one moving beyond the front porch of the frontier, the other laying claim.”2

Laying claim. And isn't it ironic that what she wanted was to be the one that stayed. She wanted to be trusted, she wanted her father to view her as like her brother who had passed away. And in this roundabout way, this is what she got. Because when everything was lost, she was the one that kept it together and claimed what was hers. And you know, the whole metaphor of the West—there are even some people that don't like the word frontier anymore—and that idea about western expansion and destruction of the indigenous populations… I still think there's a place where we can hold both things. Yes, it destroyed civilizations that were here for thousands of years, but at the same point, we had people of their time struggling to make a living and feed themselves. I mean how many of us now could say: ‘we’re going to the wilderness. Hey, here's a field and here's a hoe. Feed yourself, build a shelter for your family.’

Yeah, talk about grit.

And there's a lot less people in that region, in Stonewall county now than there were in the 1800s. You know, the children and subsequent generations moved to the cities, which is understandable. But boy, the people that stayed out there, they're tough, man. They're really neat people. When I was on book tour in that region, northwest of Abilene in the small towns, I had the privilege of going to many of them. And, you know, they're smart, bright, literate, kind humans. It was such a privilege to be able to write about their place. Where they live is important, and so I really wanted to get the details right. But I do feel like it's a love letter to my family and their grit.

I think those places and communities are off the beaten path for most people. I mean, even with the Great Resignation and people moving out of California… you know, hoppin’ Bozeman is no Montana ghost town.

It's not… and you know, going to Boulder, is not the same as going to La Junta, Colorado and Rocky Ford where they lost the water rights and that beautiful agricultural region has gone. If you really want to see our country and if you really want to understand the dynamics of people and what they want and who they are, you've got to get off the main road.

To go back to that ending, that’s no small moment for your characters. Chapter after chapter, Jessa and Nellie have been at odds. The public fallout from Jessa’s pregnancy even loses Nellie her teaching job. Do you think that reconciliation, or for that matter, family relationships are a bigger part of the book that we might realize?

Yeah, I think that's it. I mean, I tried to have those moments where Jessa’s so lonely when she first comes to the Martin’s house. She's never slept in a bed by herself…so I have three boys and they're close in age. And I remember we went back east to New York and Massachusetts, and they were just killing each other. We were all sharing this basement in my Aunt's house, and they're like, fighting over the toothpaste. And I was like, ‘I can't wait till we get home and they're gonna have their own space.’ And we got home. That first night, I walk into my youngest son's room and they're all three on the bed like puppies.

Kate laughs.

They don't know how to not be entwined because that's who they are. And I think Jessa and Nellie, they're entwined in that way that only sisters can be… for Jessa, it’s like, ‘I'm my whole self with my sister.’ And I think Jessa finding Nellie this opportunity in California was the amends. I love that word amend.

You mentioned that your father passed away when you were writing this book.

I did. So that was really interesting to be in that place of grief, and writing about sisters, writing about a mother and a daughter. So I was able to channel a lot of my feelings about my Dad—he was my step dad but he was really my Dad—and the way my Dad was… he was not a man of a lot of words, but he taught me things. And we had animals together, I was in Future Farmers of America. So I actually learned to castrate calves with my uncle Bob. So my Dad taught me a lot of things and then the part in the novel where Jessa’s like, looking forward to the two of them being outside and doing a project together. I always felt like it was such a privilege to be doing a project with him. So it’s a little bit of a love letter to him as well.

What do you hope readers will take away from ‘The Shinnery’?

Well, I hope it's entertaining! Come on, let's not kid ourselves. It's a novel to lose yourself in. As far as the things we’ve touched on go, place and family are so important. Strengthening those family ties. And if you have things that are undone or upset or unfinished, who knows? Maybe it's an opportunity to make amends and mend them.

Anything else?

We didn't talk about the faith piece too much. Someone from a book group felt like at one point Jessa loses her faith, and I thought, Oh, and I went back. And I'm reading the point where she talks about how she had shrunk God, and I don’t think she loses her faith at all. She does struggle, or perhaps she develops this idea in her head that God was approving of this thing between her and Will. But then that goes south and she comes to this point where she goes, ‘I shrunk God down to think that God gives a whit about me and Will Keyes.’ She felt she had almost spoken for God.

That doesn’t sound like a loss of faith.

Well, she says at that point, the only prayer she will offer is Thanksgiving. I don't see her as rejecting faith… reassessing, maybe. I think it grows within the story.

Are you working on anything now?

Yes. It's a story that's been in my head for a long time. It takes place in the summer of 74. And it's about a woman-–kind of like Jessa—with little agency, and little power in her life. She's made some poor decisions and she's moved to Riverside, California with a kind of controlling man. And she has a daughter…

Kate laughs.

I'm doing such a terrible pitch on this.

No, keep going.

Let's say she finds her freedom and liberation as it were. But she finds it in Avon products and being an Avon lady. At the time in Riverside, March Air Force Base was thriving. You would go into people's houses and like, oh, there was an African American family from Louisiana, or Creole, and they have the smells of their food. You know, living in your little suburban house, you wouldn't meet people like that… and so this Avon thing is this way that this woman meets people and in a sense, finds herself and is exposed to all these ideas. And also, the reason she took the job was her daughter is supposed to go on a Washington DC trip and meet the president. It’s ‘74, and her daughter is obsessed with Richard Nixon. And, of course, in August of 1974 the president resigns. So it's like everything falls apart. But then what happens? Resurrection?

Kate laughs again.

It's like the same book without horses!

I'm sure you'll have an audience for that. It’s like ‘give me the same story, only different.’

Not quite… but I think we deal with the same themes because that's what grabs us as humans. That's true for me.

Thank you Kate, that was wonderful.

Kate Anger, ‘The Shinnery,’ page 164. Bison Books.

Kate Anger, ‘The Shinnery,’ page 236. Bison Books.