As Shocking as Fiction

Macbeth, Lincoln, and dark parallels in ‘Crime and Punishment’

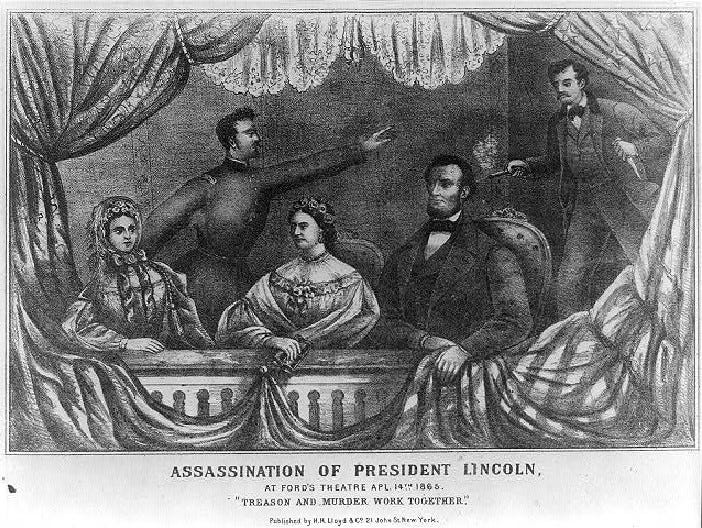

Abraham Lincoln’s fascination with Macbeth is well documented. John Wilkes Booth, respectively, was more of a Julius Caesar fan—and you might say he outdid Brutus in sheer publicity. But where that parallel thumps the forehead, the Lincoln-Macbeth connection appears to run deeper.

In an essay for Humanitas, Michael Knox Beran takes the Lincoln-Macbeth connection even further. Beran speculates that the wartime President’s personal obsession grew as he saw parts of himself in the tragic hero.

He imagines Lincoln bristling at Macbeth’s ambition:

“In his moment of triumph, at the end of a great war in which the forces under his command won an astonishing victory, Abraham Lincoln re-read Macbeth, and reflected on how costly a thing is even a just ambition. This willingness to explore, however indirectly, the darker recesses, the secret places, of his own character, this willingness to throw light upon the "black and deep desires" latent within him—at a time when lesser men would have been conscious only of the glory of the moment—is evidence of the sensitivity of Lincoln’s conscience, the power of his moral imagination, and the greatness of his heart.”1

At any rate, letters from Lincoln’s friends, and accounts from his own law partner William Herndon prove one thing—he loved the Scottish play.

With the chaos and bloodshed of a Civil War that would claim over 600,000 lives shrouding everything, we can imagine a burden-shouldering Lincoln reciting lines in which Macbeth who longs for death with chilling fondness.

“Duncan is in his grave;

After life’s fitful fever he sleeps well.2”

That Lincoln allegedly dwelled on Macbeth and King Duncan within weeks of Booth shooting him cements the connection—at least in our minds—and magnifies the tragedy of his assassination. For all the costly, if at the time, necessary missteps, Lincoln, unlike Macbeth, was no backstabbing opportunist.

Tragedy in Idaho

Real tragedies are shocking enough.

But it’s haunting when fictional equivalents seem to send up a signal flare. Rare as it is, (and we could add that both Ronald Reagan and John Lennon’s assassins had an obsession with The Catcher in the Rye), yet another literary-true crime connection is surfacing in the numbing quadruple homicide in Moscow, Idaho—a small, college town some of my readers are quite fond of.

In a coincidence as haunting as Lincoln-Macbeth, twenty-eight year old Bryan Kohberger, the primary suspect in the robbery and stabbings of four University of Idaho college resembles yet another great works character—Raskolnikov from Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment.

Since Kohberger’s high-profile arrest in Pennsylvania, Dostoevsky fans, and a few adept Moscow residents have made the connection. Furthermore, the crime itself, a grisly, isolated four A.M. attack that left Madison Mogen, Kaylee Goncalves, Xana Kernodle, and Ethan Chapin dead in the house they rented mirrors the novel’s infamous double murder.

Thus far, and while Kohberger (with some are already likening to serial killers like Ted Bundy) is far from proven guilty, they’re not wrong.

As a guide for piecing together what might have happened, (should we note the settings—Moscow, and in Crime and Punishment, St. Petersburg?) the novel and its rascally main character prove all too tempting.

On this note, and if reading over a few details of the homicides and their primary suspect hits close to home, consider this your offramp. I’ll start the Venn Diagram with Crime and Punishment, a novel in which plot, psychology, character motivation, and spiritual inquiry all twist and snap rapidly, like a master solving a Rubik’s cube.

If you’d like an eight minute primer on the novel’s main character and why it’s worth reading, I’d recommend this snippet from an old classroom lecture by Jordan Peterson.

From the Crocodiles:

We take time out of professional schedules to write, curate, and publish these guys twice a month. If you enjoy reading them and if you’re so inclined, please consider donating to the tip jar or becoming a patron of ‘Shelf of Crocodiles’ with a small, monthly donation.

To our three founding patrons, thank you, thank you, thank you.

And thank you for sharing, liking, promoting and subscribing.

A Template for Evil

Around page eighty, Crime and Punishment starts in earnest when Raskolnikov kills and robs a miserly pawnbroker. Having scoped out her apartment as a regular customer, he judges, not wrongly, that she’s something of a parasite. Her place is stuffed with treasure, money and possessions that people in the neighborhood pawned out of desperation. Broke, delirious, and furious that his sister is marrying a government official to support the family and subsidize his own law studies, Raskolnikov kills for money, thinking in terms of a Robin Hood equation.

But it’s also personal.

Murdering the old crone is Raskolnikov’s way of testing a flimsy, almost Nietzschean theory that extraordinary people—those slated to play a large role in advancing humanity’s interests—get a pass on moral boundaries.

Crackpot as it sounds, it’s also brilliant—a kinetic personification of the ideas circulating around Europe and Russia in the late 1800’s. We immediately recognize how insidious it is, and how it appeals to insecure, unskilled, and perceptive young adults like Raskolnikov… and a few of those higher specimens on the Antifa bell curve. Of course they, like Raskolnikov, like any of us, and quite possibly like Kohberger, who was obsessed with crime and criminals, rank among the extraordinary. Anointed, as Thomas Sowell might say, to fight injustice and guide the Godless, lumbering masses to New Jerusalem, violence on their part is justifiable.

Just, we might add, as it was for Mao, Hitler, and Stalin.

In Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky’s 1992 translation, (the one I read about a year ago), the sequence when Raskolnikov casually, and even arrogantly explains his theory to a police detective lights up his motivation like a signal flare:

“Raskolnikov smiled again. ‘I merely suggested that an ‘extraordinary man’ has the right… that is, not an official right, but his own right to allow his conscience to step over certain obstacles, and then only in the event that the fulfillment of his idea—sometimes perhaps salutary for the whole of mankind—calls for it…

In my opinion, if, as the result of certain combinations, Kepler’s or Newton’s discoveries could become known to people in no other way than by sacrificing the lives of one, or ten, or a hundred or more people who were hindering the discovery, or standing as an obstacle in his path, then Newton would have the right, and it would even be his duty to remove those ten or a hundred people, in order to make his discoveries known to all mankind. It by no means follows from this, incidentally, that Newton should have the right to kill anyone he pleases, whomever happens along, or to steal from the market every day.”3

In a blinding flash, we see why he did it.

With the theory in tow, Raskolnikov masked his own quivering desperation in a kind of utilitarian nihilism—and committed himself to a more thrilling, and ultimately, self-devouring course of action than, say, getting his grades up.

Both fictionally, and as an amalgamation of the secular ideologies that would tear Europe apart in the Twentieth Century, Dostoevsky shows us the smoking gun. And in the deft, jarring description of Raskolnikov’s double murder, he brings it down to the human level.

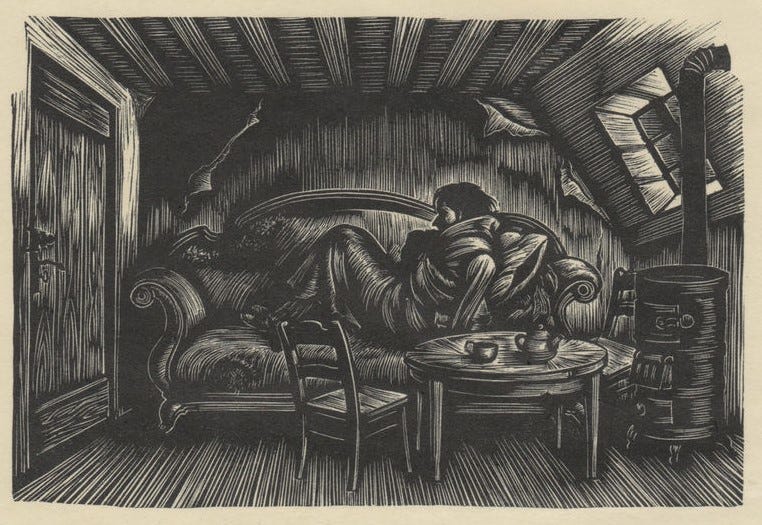

Foaming with adrenaline, and nearly demon possessed, Raskolnikov enters the pawnbroker’s apartment, waits until she turns her back, and then clubs her to death with an axe. When the pawnbroker’s deaf sister stumbles on the scene, his plans go out the window. After murdering her too, and with shouts from neighbors and someone ringing the doorbell, he forgets the robbery and flees with next to nothing. From there, and with suspicious characters and detectives all wheedling him, Raskolnikov stumbles through a hellish maze of his own guilt.

Chilling Parallels

Though dissimilar on many counts, the U of I murders and their primary suspect bear a striking resemblance.

They occurred at a private residence, and without forced entry (the pawnbroker lets Raskolnikov in after he shows her a silver cigarette case). They were violent. An affidavit from Moscow Police Officers describes two deceased victims in a second story bedroom, and two more in a third story bedroom—all with stab wounds. Officers found a leather knife sheaf, a piece of evidence that’s been linked to Kohberger through DNA and genealogy, next to two victims.

Raskolnikov’s weapon, which he does not leave behind, is a pilfered axe.

While Raskolnikov is interrupted, and nearly seen by other people in the building, police confirmed that two more roommates were at the Moscow house that night. One of them claims to have seen the suspect—a figure “clad in black clothing and a mask’ and ‘5’10 or taller, male, not very muscular, but athletically built with bushy eyebrows.” That the same roommate also heard crying, commotion, Kaylee Goncalves’ dog barking, and a male voice saying ‘don’t worry, I’m going to help you,’ teases another parallel.

Like Raskolnikov, Kohbeger may have improvised.

Perhaps he was discovered; perhaps he attacked others he hadn’t planned to.

Here, strong evidence against Kohberger suggests that he, like Raskolnikov, visited the crime scene many times before acting. While Kohberger’s phone was off, or on airplane mode at the time of the murders, mobile data found it close to the house eleven times in the months prior, each time in the evening. Footage outside the house showed a white Hyundai Elantra driving away within twenty minutes of the roommate’s encounter with a masked figure. Authorities found the same car at Kohberger’s apartment, registered in Washington but with a Pennsylvania license plate.

That same car, apparently cleaned, made an appearance when Kohberger was arrested at his parent’s house in Eastern Pennsylvania. Like Raskolnikov, who nearly passes out when local police call him to the station and casually discuss the crime, Kohberger made strange, nervous conversation with those who arrested him.

With the connection in mind, and ignoring the clear difference of victims—fictional, solitary adults versus four promising, very-real college students—it’s easy to let the search for confirmation run away with itself.

But that doesn’t erase further similarities.

Raskolnikov studied (or tried to study) law. Prior to his arrest, Kohberger was a lonely, intelligent, and often sleep deprived doctoral student at Washington State’s criminology program. To Raskolnikov’s brooding curiosity and intelligence, former teachers praise Kohberger’s strong passions for policing and criminal justice. He applied to, but was not offered an internship with the Pullman, Washington police department.

Before he moved to Pullman, and when Kohberger was a Master’s student in Pennsylvania, his curiosity about crime bordered on obsessive; that he once posted a reddit survey asking former prisoners how they choose victims nearly says it all. Peers, and in one instance, a Tinder date, recall awkward, even aggressive behavior.

While Dostoevsky doesn’t flesh out his character’s childhood, accounts of Kohberger’s high school years are already surfacing. As classmates tell it, he struggled with heroin, lost a ton of weight from one year to the next, and became a bully after making friends proved too difficult. That Kohberger’s family, like Raskolnikov’s long-suffering mother and sister, appears stable, supportive, and shocked at his arrest pushes the resemblance further.

Reading Further

If Raskolnikov, with his disdain for responsibility, and the quivering urge to prove himself through callous violence captures a type it’s a highly adolescent one. As Kohberger may, or may not be the culprit, it’s too early to tell if he’s a Raskolnikov—or another type altogether. This early, with a summer trial planned and murmurs that he’ll plead not guilty, any conclusions are highly presumptive.

Meanwhile, four stricken families grieve an unfathomable tragedy.

While it may be trite, and little consolation for a shocked town, are there more, and deeper truths in Shakespeare and Dostoevsky than we realize? And in the Christian Gospels that an imprisoned Raskolnikov reads in Crime and Punishment’s final chapter? Earlier, and before he finally confesses, a loyal, long-suffering prostitute reads him the story of Lazarus rising from the dead—and for a moment, Raskolnikov calms himself and listens.

Is there more hope than inner darkness?

In a strange world filled with darkened hearts, Dostoevsky, the grand inquisitor, insists there must be.

Michael Knox Beran, ‘Lincoln, Macbeth, and the Moral Imagination,’ Humanitas.

Macbeth, Act III, scene ii.

Dostoevsky, ‘Crime and Punishment,’ Pevear and Volokhonsky. Pages 260 - 261

Excellent and thought-provoking. Thanks for these insights, Curtis!

For a more in-depth look at Raskolnikov, his solipsism, and his final, almost miraculous transformation,

(he goes from obsessing over self-actualization to seeing his worth in how someone else loves and sees him), Marilyn Simon's article in Quillette is worth a read:

https://quillette.com/2023/01/31/crime-and-punishment-and-redemption/?ref=quillette-newsletter