Ibsen Follies

‘An Enemy of the People’ certainly has Covid parallels—but those sitting in $1,000 seats got them completely wrong.

A hundred and thirty years ago, playwrights punched above their weight. From the 1880’s through the 1920’s, plays, theaters, and acting schools like the Moscow Art Theater steered culture and shaped the drama we consume today. Historian Paul Johnson argued that theater, more than any other art form, molded the modern mind.

The fact that Europe’s tradition-bucking dramatists—Ibsen, Chekhov, Strindberg, and later Brecht and Beckett—liked Christianity as much as the 2024 Paris Olympics isn’t surprising. Going back to Athens, theater has always danced on the margins. Draped in revolt, their plays tossed out Europe’s long-entrenched faith and traditions for Enlightenment substitute: a murky witches’ brew of doubt, moral relativism, Darwinian naturalism, and personal liberation at any cost…

As always…

Thank you for reading!

To support this content—or as I like to put it, feed the crocodiles—consider upgrading to a paid description. You can also get in touch with me about one-time donations; a handful of my readers prefer to support me that way.

A like, a share, a comment, a restack, or a shout on social also goes a long way.

…Like a batch of acetone, this new religion stripped drama bare. Complex individuals, psychological intensity, and the tension in everyday events took front and center. Action onstage grew lean, pointed, and politically edgy. Heroes, cartoonish villains, playful subplots, and showy sets and costumes fell by the wayside.

As form and style turned against the grain, worldview followed. Everyday settings and trimmed down plots paired nicely with outcast characters—martyrs crushed by church, family, patriarchy, or the social-moral pressures of bourgeois society.

For every rant about Hollywood’s anti-Christian animus, these secular roots aren’t really discussed. To casually read Ivanov, Miss Julie, or A Doll’s House is to preview the assumptions that those with green hair and TikTok followings casually take for granted. It’s also a pill and ice cream lesson—novel ideas, wrapped in art, really catalyze. A century and a half later, film and theater folk revere secular humanists as patron saints, and Europe’s rejection of anything resembling a Christian approach to family, behavior, moral standards, or the universe is long and total.

America’s own, noisy rejection of the Christian worldview (as with most things, we follow Europe but take our time), may still define our age… but I digress.

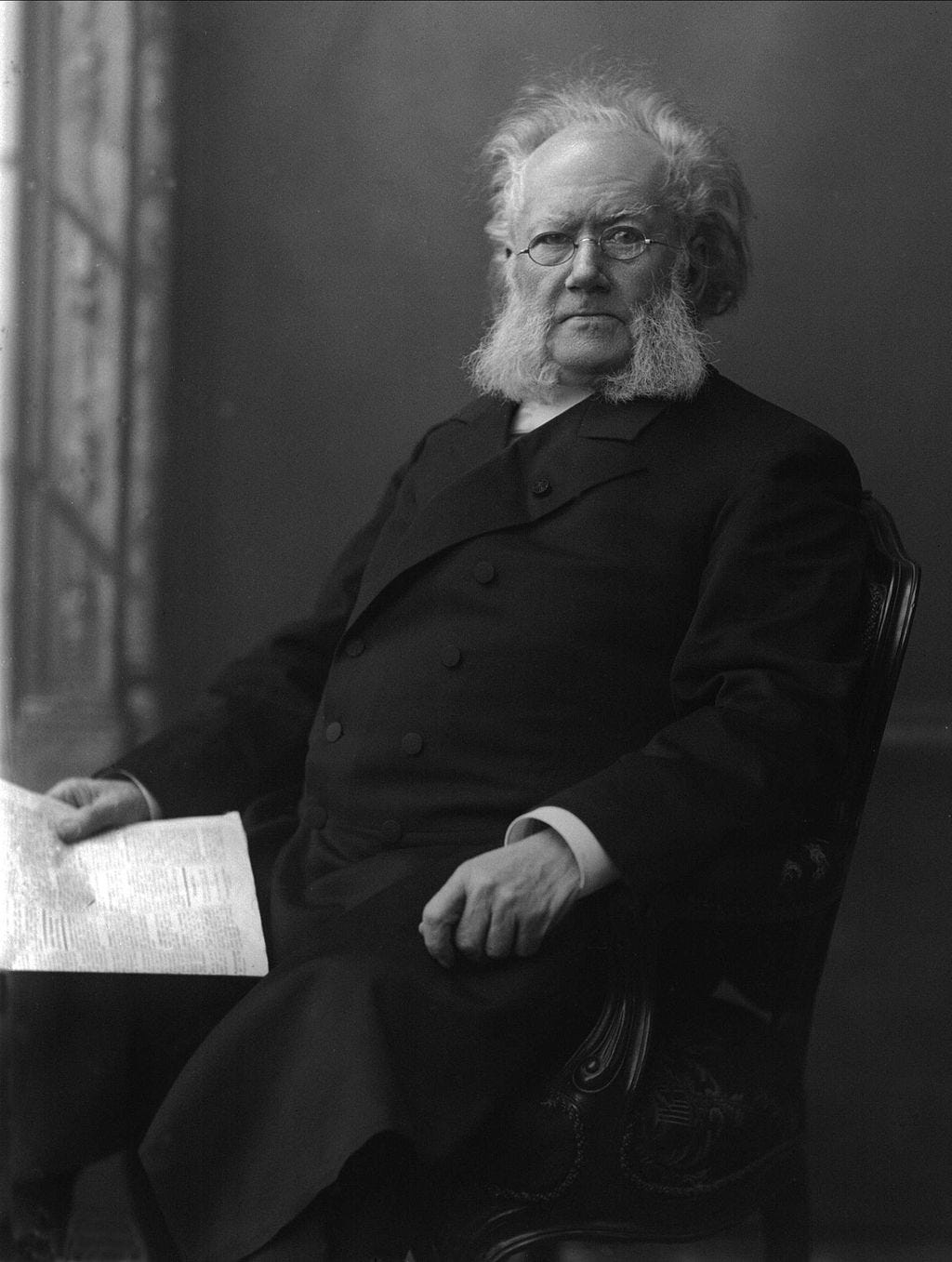

Henrik Ibsen

For all this, and for a surprising Broadway hit, we have one playwright in particular to thank—Norwegian heavyweight Henrik Ibsen. Writing from a backwater region, and in a language few across Europe understood, Ibsen’s works went on to shake the continent. He’s the author of A Doll’s House, Brand, Hedda Gabler, The Master Builder, the epic verse-drama Peer Gynt, and the now-trending An Enemy of the People, to name a few.

Sparse, striking, and pointedly climactic, a play by Ibsen is a masterclass. By some counts, the ‘Father of modern drama’ is performed as frequently, and in as many locales, as Shakespeare. The plays drive the modern gospel of personal liberation home so well that drama professors, social critics, and even hipster playwrights (see A Doll’s House, Part Two) can’t get enough of him.

In a blunt 2005 essay, Theodore Dalrymple dubs Henrik Ibsen the first postmodernist. A doctor who practiced in British slums, Dalrymple calls A Doll’s House out for its destructive wake (it famously ends with the wronged, disillusioned Nora Helmer leaving her husband and children for good.)

“When, as I have, you have met hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people abandoned in their childhood by one or both of their parents, on essentially the same grounds (“I need my own space”), and you have seen the lasting despair and damage that such abandonment causes, you cannot read or see A Doll’s House without anger and revulsion.”

-Theodore Dalrymple, ‘Ibsen and His Discontents’1

For better or for worse, the legacy is undeniable.

Paul Johnson went even further in Intellectuals, calling Ibsen’s plays a ‘keystone in the arch of modernity.’ More than anyone, Johnson argued, the pugnacious, brooding Ibsen changed turn-of-the-century minds, cementing the progressive, self-righteous revolt against everything Europe (and increasingly, America) regarded highly. Critic Harold Bloom, who includes a chapter on Ibsen in his The Western Canon, saw a messianic streak in this revolt—and also likened him to trolls.

With all this in mind, Broadway, and director Sam Gold reminded us how potent, and likely to be misapplied, Ibsen remains. This spring, a revival of An Enemy of the People with Michael Imperioli (Chris from The Sopranos, looking older) and as of a few weeks ago, Tony winner Jeremey Strong, scaled the New York stratosphere.

In other words—and in a headline that makes this theater nerd stand taller—a hundred-year-old, lesser-known drama by a dead white male broke though Broadway’s vapid lineup of woke, showy musicals… and beat the tar out of Hilary Clinton’s femi-show Suffs. As things go in the starving theater world, ‘success’ barely describes people flying in from London or Dubai to claim $1,000 seats for a show that isn’t Hamilton.

As the saying goes ‘we’ll take it.’ But having said that, those comparing the play to the Covid-19 pandemic walked into the hardest self-own we’ve seen in a long time.

If you’d like a preview, I’ll put it this way: ‘An Enemy of the People’ certainly has Covid parallels—but those sitting in $1,000 seats got them completely wrong.

‘An Enemy of the People’

Plays like ‘Enemy’ are neither difficult, nor (being public domain) expensive to stage. Ibsen’s setup is particularly evergreen. That’s a net positive in that words and actions speak clearly for themselves, and for newer audiences over time. As things go in tory, lockdown-supporting Manhattan, it’s also a liability.

At any rate, think of the play as Ibsen’s Erin Brockovich.

In a small, close-knit town, whistleblower scientist Dr. Stockmann discovers that the water supply of a small town’s burgeoning health spa industry is tainted with bacteria. Confident of his findings, he first goes to his elder brother Peter Stockmann, the town’s mayor. Realizing what’s at stake, Peter warns him to back down, less rumors of bacteria-borne illness spook the spa’s financial backers. Repulsed, Dr. Stockmann takes his findings to Hovstad, editor of the town’s newspaper.

In clean, Oedipus-style reversals, Dr. Stockmann’s supporters fall like dominoes. One by one, they succumb to the pressure of social consensus—like the early Covid lockdowns, there’s no no questioning. The spa is sound; the promise of jobs and regional growth leaves no room for whistleblowers.

Stunned, at first, that people aren’t thanking him for preventing illness, the scales fall from Dr. Stockmann’s eyes at a town hall meeting, when the masses (thanks to his mayor-brother) turn on him like attack dogs.

But unlike Oedipus, who famously finds himself as causing the plague on Thebes, Dr. Stockmann does not back down. Here, Ibsen’s tilts tragedy into his own brand of progressive melodrama, turning Dr. Stockmann’s into a secular Moses. Ruined financially, abandoned by friends and allies, he answers the call to misery and persecution for bearing the truth. When an angry crowd surrounds his home and throws rocks through the window Dr. Stockmann rallies his family to join him:

“We must be careful now. We must live through this. Boys, no more school. I’m going to teach you, and Petra will… remember you are fighting for the truth, and that’s why you’re alone. And that makes you strong. We’re the strongest people in the world…”

-Dr. Stockmann, Act III2

It’s as religious an ending as Ibsen’s realism can muster, and it strikes the chord of Moses telling everyone it’s time to leave Egypt. In this recent translation—one by star playwright Amy Herzog—Dr. Stockmann laments ‘this would never happen in America.’

There, and in a parallel that boggles the mind, the lockdown-supporting intelligentsia sees itself, and even glimpses of former hero Anthony Fauci:

“Best of all is Jeremy Strong’s Dr. Thomas Stockmannn, who vividly recalls Dr. Anthony Fauci, especially when this good Norwegian doctor is warning a town about the dangers of an impending epidemic.”

The mob, of course, the ones shouting down Dr. Stockmann and hurling rocks through the window, are the deplorables—the mRNA vaccine naysayers that late-night comedy love to mock, while simultaneously bending backward to make lockdowns and coerced medical experimentation seem normal.

Stage chops notwithstanding, Michael Imperioli likened the play’s violent mob to January 6 rioters in an interview.

In other words, ‘An Enemy of the People’s’ clear warning about standing up to those who will not, cannot accept what they don’t want to hear, vindicates CNN watchers—those who trusted CDC science, supported vaccine mandates and tuned in to the televised, nakedly partisan January 6th committee.

To hear and infer these takeaways is more of a window into the affluent, managerial mindset than one can stomach. As the Bible, Shakespeare, Breaking Bad’s Vince Gilligan—and even, to a lesser extent, Henrik Ibsen—remind us, our ability to absolve ourselves, to rationalize our motives and intentions in order to think well of ourselves is limitless.

From Oedipus to the Old Testament and on to Breaking Bad, great drama shows us this with a scalpel.

Speaking of Parallels

While the parallels between Dr. Stockmann of the most of devout of Covidians are certainly there (if you can indict a ham sandwich, you can certainly draw them), I’d like to think Ibsen would notice something strange about hip New Yorkers exonerating their pandemic measure enthusiasm by comparing his hero to Fauci. Lest we forget, Ibsen did not take kindly to seeing his plays shoehorned into social-political causes. When feminist societies around Europe honored him for A Doll’s House, he memorably insisted that it was not, in any way, a work promoting feminism.

Still, if we think about ‘Enemy’—a man of science ridiculed, stripped of everything, and physically threatened for bringing (in Al Gore’s choice words) an inconvenient truth to people who won’t hear it?

That sounds an awful lot like Jay Bhattacharya, one of the authors of the Great Barrington Declaration in October of 2020.

Exiled professionals who stepped out line on masking, vaccine mandates, or DEI struggle sessions also come to mind—or whistleblowers thrown in the crosshairs for reporting hospitals who push transgender ideology and sterilization on minors. If the Ibsenian hero goes through grief for sharing something dangerous, and if the villains are vested, beneficiaries of said dangerous thing, then who are we talking about, exactly?

If we have to go there, who has been who these past few years?

While I’m not suggesting a production would be better staged with Dr. Stockmann dressed like Jay Bhattacharya—if any theater company wants to really be as brave and transgressive as the community claims to be, have at it—Fauci and the CDC’s own admissions should tell New York audiences that they’ve grasped the knife by the blade.

That’s another way of saying Ibsen, his plays, and even his messianic revolt against traditional institutions is more nuanced, and perhaps biting, than the gatekeepers realize. As for those mumbling about ‘pandemic amnesty’ while comparing Dr. Stockmann to Fauci, a place to start the healing might be resisting the temptation to turn muscular, evergreen drama into a kind of boutique palliative.

Until they admit their adamant support establishments that ruled like a mob, and pulled out all the stops to ruin Dr. Stockmanns not long ago, all the reason and revolt Ibsen can muster will fall on deaf ears—their own.

‘An Enemy of the People’ is a swell pressure cooker. With one situation, and a close bubbling of consequences, we’re boiling by the time the curtain falls. That’s enough to leave anyone watching with some thorny questions:

Where does moral action, urged on by the truth, end… and where does the pride of not wanting to be wrong take over?

Can we trust others when the chips are down? How about ourselves?

What safeguards might protect whistleblowers, and help prevent a tragedy of the commons?

But interpreted in a way that lionizes elites—those with power and connections who panicked, forced that panic on everyone else, and to this day remain shielded from the consequences of that panic—Ibsen’s cutting work wilts to melodrama.

Which Way, Playwrights?

If conservatives, Christians, and anyone wanting to return drama to it’s truth-telling, human nature-peeling role care about the arts, there’s an obvious takeaway here.

It’s time to make, and stage, our own theater.

Stage Shakespeare. Stage Arthur Muller. Stage Ibsen—why not—with no agenda, and leave the audience to extrapolate as they well. Stage the Bible, mystery-play style—or write our own plays. Whatever we choose, do it well, with dialed back political agenda (or not, with a few exceptions theater of the right is nonexistent), and see if we can make the audience laugh or cry.

Build it, in other words, and the audiences who dropped off the map during the pandemic might come back. As long as our nature and society remain, shall we say, subpar, then there’s a reason to go to the theater and see dramas unfold.

As for influence, plays and playwrights may be lightyears behind the smartphone.

But until Christians reckon with modern drama, as in, go head-to-head with the Ibsens and Chekhovs who bought the property while secularizing it for a century, expect more missing out on the action. More Hallmark movies and C.S. Lewis monodramas for us on the one hand, and professional theater for and by secular elites on the other… priced accordingly.

When we enter the arts and give dead European playwrights a run for their money, powerful works by Christians might earn a place onstage. With any luck, and with a God who toggles ‘cheat’ codes, truth-starved audiences can grapple with what they need to see and hear.

That, as it did before in Europe, is one way to swing hearts and minds.

Until then, there’s always ‘Suffs.’

Theodore Dalrymple, ‘Not With a Bang But A Whimper.’ Page 64.

‘An Enemy of the People,’ adapted by Arthur Miller. Page 124.

Brilliant review! This is incisive analysis of the decline of contemporary theater. I subscribed!

You wrote a great essay on the ideals that have been pushed through the stage into our culture! Sure, a lot of people have missed the point of some of these plays (your point about Enemy was fascinating); it's the classic case of people only hearing what they want, lol. I love that you followed it with a call to action for Christians to get some good stuff on the stage.

Why is it that we (Christians) are consistently floundering when it comes to putting out stuff that is good without being hokey? I love to find eternal themes in movies and plays, but for some reason, when they are intentionally placed there, they end up being ... I don't know ... too on the nose, maybe (e.g., anything with Kirk Cameron). The movie Warm Bodies is a zombie version of Romeo and Juliet, however, there are so many Christian themes in there that it's almost a replica of the Gospel. But that certainly was not the intent the writers had when they wrote it. And, admittedly, I'm probably just as bad as the folks misinterpreting Enemy in your essay. Maybe I just hear what I want, lol.