Gear up, Crocodiles.

Last month, Noah Elkins kicked in the poetry door with George Herbert’s Easter Wings. With a few more seventeenth-century stanzas lined up, I dare say we’re not done yet. To tease out a timeless subject, evergreen for Christians, devotional poets, and skeptics alike, I’ll preface Herbert’s stanzas with quotes from a more recent coming-of-age novel: W. Somerset Maugham’s Homeric, semi-autobiographical Of Human Bondage.

I know—you can’t always mix old and new.

If it sounds like I’m pouring barrel-aged scotch and yesterday’s zinger of an IPA into the same jug, bear with me. Timeless subjects please any palette, and this one’s for the ages—heart yearning, and its familiar consequent, disappointment. To both broaden and narrow the category, I’m not talking about sexual desire per se (if I cared two whits about Pride Month, that’d be fitting, wouldn’t it? Too bad I don’t.)

While we’re at it, it’s one year since the Dobbs ruling, and if anything, that makes this Dobbs / Life Month. Talk about something to celebrate.

I digress.

Rather, or perhaps even beneath sexual yearning, by heart yearning I’m talking about complex, subterranean needs and wants. Possessing someone or pleasing them, winning approval, actualizing a pristine vision, knowing one’s desires and having them perfectly known—all the deep-seated drive decisions and relationships, guiding much, and no doubt too much of our actions in this late, decadent age of follow-your-heart. Most poetry, drama, and fiction from the Romantics onward deals with this stuff in one way another.

If not the overarching subject of modern literature, it’s a wonderfully broad bullseye.

In the words of stick-up artist Omar Little: “At this range? With this calibur? Even if I miss, I can’t miss.”

Different Backgrounds

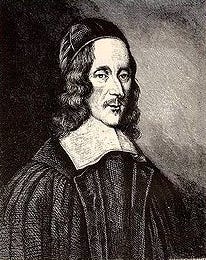

Where Herbert yearns after the God of the Bible (a yearning formalized by his final years as an Anglican rector at two small churches), his poems raise up relatable themes of desire, penitence, self-judgment, disappointment, and ultimately joy. That Herbert wrote his poetry— ‘The Temple’ starting with ‘The Altar’ is his most prominent collection—as Christian devotion, and prior to the shifts that made human reason and human fulfillment the measure of everything, doesn’t diminish his worldly knowledge. From grief and longing to his own shortcomings, the heart’s wants and ways are too familiar to him.

W. Somerset Maugham, by contrast, and through his semi-autobiographical protagonist Philip Carey, gives us the gladiator’s approach. His characters chase their heart’s desires to often bitter endings, and with each disappointment, a kind of sorrowful wisdom accrues. While secular, God-absent heart yearning starts with a kind of freeing optimism, it usually, and ultimately bends tragic.

On this note, the most truthful, instructive, post-Christian stories about ‘follow your heart’ tend to be the Breaking Bads of the lot, the ones with a moral universe that lets the heart’s true, ghastly shape come into focus. Because deep and hidden desires—particularly around identity—still have a kind of sanctity about them, skillfully fleshed out characters who that follow heart yearning to the bitter end are more instructive that we realize.

Turning back to Herbert’s enchanted, Christian universe, the pain-ridden, but wonderfully vibrant hope of the Christian gospel (unless someone else rose from the dead and is being coy about it, nothing else comes close), that bitter end to heart yearning is nothing less than an open door.

Or rather, a backdoor to a grand, palatial estate.

Of course, getting there is no less of a ringer, and Herbert’s poem ‘Love Unknown’ takes us, as it takes every Christian heart, right through it.

But before we dive in…

Word on the Pond:

Shelf of Crocodiles is no longer taking donations via Ko-fi.com.

Rather, and with a traditional, Substack paid subscription option in the works, you can support this content by sharing it, re-stacking, commenting, following on Twitter, or forwarding this email to someone who might like it.

For now, if you’d like to do more than by joining our rank of financial patrons who lend annual support, then give me a shout. The more you feed the Crocodiles, the more they can make happen.

For the record, they just loooove new readers.

Why Everyone is One Huge Tease

A few years ago, my wife pinned down heart yearning (or at least a lion’s share of it) with one brilliant question:

“Who’s someone you could never spend enough time with?”

After sifting through our combined lives in Texas, SoCal, Idaho, Taiwan, the U.K., and of course, Sacramento, we came up with a few names each.

But that was it.

As author N.D. Wilson puts it, ‘our days pile up like leaves.’ Busy as we are, and the older we get, life decides for us. Kids grow up, loved ones pass. Dear friends come and go. Sadly, the general flow of things often keeps us from connecting deeply, to the point of liking someone’s company as to never have enough of it, with that many people. So when someone’s interests, conversation, or mean sense of humor unlocks our own like a skeleton key, the heart pays attention.

It’s not finding another like that around the corner.

Of course, I’m not putting down essential relationships. Family. Spouses. Brothers and sisters in faith or long-running colleagues. Tended well, those bring satisfying connection—but they’re not always answers to my wife’s question. When they are; that is, when someone in our day-to-day fabric starts to fill that void completely, the results often disappoint (think of Jacob pining for Rachel), or they really rock the boat (Jacob favoring Joseph and stoking everyone’s jealousy).

Ordered well, and aligned to God’s framework or a more selfless goal, those relationships get better and better, simmering like a fine crockpot meal. But at the same time, in his description of friendship—something that, unlike family bonds, arises from side by side companionship, when ‘one man says to another, ‘What! You too?’ —C. S. Lewis reminds us that the heart craves likeness and connection.

For rugged, go-it-alone types, the question might be a non-question. All the same, and if not equally balanced by a longing for being master of one’s fate, the longing for connection persists in other ways. Or if someone’s honest answer is that they could never spend enough time (or at least, not enough of an exclusive, transdimensional lunch) with some brilliant mind passed into history, (a C.S. Lewis, or for math lovers, a Sir Isaac Newton), that’s not no answer.

In one of his sermons, the late Tim Keller put it another way: ‘think of someone who’s smallest praise would lift you to the skies.’ Even if you’re not hung up on anyone in particular, (in which case, you’re probably hung up on yourself), someone whose words or presence come with that effect is probably out there.

Elsewhere, Keller’s notes that deep down, we want to be uniquely (not broadly, or mistakenly) loved and uniquely known. That is, and for all our warts, appreciated, admired, and fully reciprocated by someone we esteem. That being perfectly, or even adequately loved and known happens infrequently, or not as often, or not with the person we’d prefer, might be life’s biggest tease. Factor in the fact that our heart’s strike zone changes over time, if not one-eighty degrees than to the point where the initial person / audience we yearned for no longer gets the job done.

Just ask King Solomon.

Or ask Jacob, who finally bedded his Rachel, only to find it was Leah all along.

Regardless, and picturing someone who will finally get it, or some pristine circumstance that will make our long slog worthwhile, the heart bides its time. That the chase itself is a subject of great, and tragic, literature should direct us to the Bible’s oldest warning.

Watch the heart carefully.

From the Commonplace

Ladies and gentlemen, on this very subject, Emily Dickinson.

The Soul selects her own Society —

Then — shuts the Door —

To her divine Majority —

Present no more…… I've known her — from an ample nation —

Choose One —

Then — close the Valves of her attention —

Like Stone —Emily Dickinson, c. 18621

Heart Yearning in Literature

If you’ve never brushed against someone (real, deceased, imagined) you could never spend enough time with, don’t worry.

Coming-of-age literature is here to help.

In a striking portrait of the real thing—and in a reminder that heart yearning is as much a mystery to the yearner as to anyone else—W. Somerset Maugham weaves an early sublot of his novel into a kind of heart fable. The yearner of course, is young protagonist Philip Carey. As far as the whole novel (which I’m still reading) goes, epic heart yearning drags Philip all over the place: first to Paris where he tries his luck as an artist, and then back to London for a medical career, and then to a life-marking relationship with a waitress and tease of a lover named Mildred.

The title itself suits, and seems to haunt Philip, both when he’s older and when he’s young.

Of Young Philip’s Bondage

Orphaned when his mother dies, Philip is raised by a strict Uncle and a timid, overly-doting Aunt. At the private boarding school, a club foot that makes him unable to play sports or keep up with the other boys. Bullied and ostracized, he constricts into his shell like a tortoise.

But when Rose, a boy decent enough to look past the disability and spend time with him, comes along, all of Philip’s heart valves dilate at once:

“I can’t walk fast enough for you,” he [Philip] said.

“Rot. Come on.”

And just before they were setting out some boy put his head in the study-door and asked Rose to go with him.

“I can’t,” he answered. “I’ve already promised Carey.” He looked at Philip with those good-natured eyes of his and laughed. Philip felt a curious tremor in his heart.2

A tremor is right.

When Rose’s choice to stick by Philip is nothing less than an emotional, social Medi Vac—Rose dignifying Philip instead of bullying him prompts other boys to treat him better—we hardly blame Philip for finding a new lease on life.

In a little while, their friendship growing with boyish rapidity, the pair were inseparable… wherever one was the other could be found also, and, as though acknowledging his proprietorship, boys who wanted Rose would leave messages with Carey. Philip at first was reserved. He would not let himself yield entirely to the proud joy that filled him; but presently his distrust of the fates gave way before a wild happiness. He thought Rose the most wonderful fellow he had ever seen.3

When the two boys leave school for break, Philip makes Rose promise to meet him at the train station before returning to school. Rose never shows, and Philip waits for hours—long enough for his milky, newfound joy to start going bad.

Soon enough, and with the object of his heart’s joy failing to deliver on the level he needs, Philip’s gratitude turns to entitlement. What starts out as wonderful becomes a source of disappointment.

At first Philip had been too grateful for Rose’s friendship to make any demands on him. He took things as they came and enjoyed life. But presently he began to resent Rose’s universal amiability; he wanted a more exclusive attachment, and he claimed as a right what before he had accepted as a favor. He watched jealously Rose’s companionship with others; and though he knew it was unreasonable could not help sometimes saying bitter things to him. If Rose spent an hour playing the fool in another study, Philip would receive him when he returned to his own with a sullen frown… the best was over, and Philip could see that Rose often walked with him merely from old habit or from fear of his anger; they had not so much to say to one another as at first, and Rose was often bored.4

Over the next chapter, the friendship ends as briefly as it starts. Hurt, possessive, and now embittered, Philip dies a kind of death in realizing that the life-giving nature of the friendship only goes one way. Before long, the two drift apart. A few chapters later, Philip is obsessively planning to graduate early, eschewing his Uncle’s expectation of Oxford to study on his own in Germany.

As much a fable as Jacob or Joseph, Maugham’s subplot takes us over dangerous ground. The wounded, needy heart is both jealous and fickle. Hung up on someone, or something like a flesh wound on a bandage, the disappointment oozes out too easily.

Rose’s interlude reminds us that friendship, and even a friendship that fills two friends deeply, might be more delicate than it looks. There’s room for wear and tear, but with too much weight and the hairline fractures come out.

In yet another favor, Maugham reminds us that getting what the heart wants often means having it turn to ash, right there in our hands. A little later, the gods torment scheming, overachieving Philip by letting him have his way.

When the headmaster finally grants his request to graduate early, skip the school’s matriculation ceremony and head to Germany, Philip realizes he doesn’t want to.

“Very well, I promised to let you if you really wanted it, and I keep my promise.”

Philip’s heart beat violently. The battle was won, and he did not know whether he had not rather lost it.

“Well, you must come and see us when you get back.”

He held out his hand. If he had given him one more chance Philip would have changed his mind, but he seemed to look upon the matter as settled. Philip walked out of the house. His school-days were over, and he was free; but the wild exultation to which he had looked forward at that moment was not there. He walked round the precincts slowly, and a profound depression seized him… he asked himself dully whether whenever you got your way you wished afterwards that you hadn’t.5

From there, in Germany, Bohemian Paris, and later on, London, Philip’s heart tilts at one windmill after another.

Here, outside of Christianity, and with the only, semi-ultimate, but mistaken answer being look within yourself, what’s a liberated, free-thinking heart yearner to do? Aside from chasing down the next thing and squeezing it until it breaks?

George Herbert’s ‘Love Unknown’

Milton, Shakespeare, Donne, Bunyan—with more than a few household names, the late sixteenth / early seventeenth century seems to tower over the rest in English literature. Though he was a contemporary to those greats, George Herbert probably doesn’t come to mind (his surviving persona ‘holy Mr. Herbert’ cemented his legacy as a devotional poet). This far into post-Christendom, and with church history having not been universally taught for generations, that makes sense.

If remembered, Herbert’s poetry is easily lumped in with all things old, or old and Christian. Unlike Shakespeare, (although even he’s on his way out…) you could have easily majored in English and never heard of him.

Think ye olde Hallmark channel, only tough to read.

But any serious reader missing Herbert is missing out on a gem. His wit, frankness, and verbal, if occasionally visual symmetry bely great skill and reflection As we’ll see, Herbert’s Christian themes and subjects often begin worldly—his own sin and laziness are two common starting points.

But from there, and unlike those who follow their hearts to tragedy and disappointment, Herbert looks up, and squarely, at the Christian hope. Though it’s not one of his greatest hits, ‘Love Unknown’ makes this climb more gracefully, and with plainer, touching pathos than many of his other poems. In it, Herbert captures life’s pain, (his ill health, his mother’s death, the financial struggles that persisted even with a stint in parliament, and a coveted position as orator of Cambridge) and the Christian’s joy. Along with all that, Herbert nails sanctification in one searing conceit—someone giving their heart away only to have it physically wrung, scalded, and pricked with thorns.

The Poem, The Poem…

Herbert frames this gauntlet in a clear, almost Medieval Christian setup. He’s the speaker, and he approaches a Master he loves—none other than God himself—and seeks to please him with a plate of fruit. If we take the plate of fruit as Herbert’s ‘works,’ the end products of his own devotion and virtue, then the yearning here is every Christian’s tiger trap. Herbert, deep in his heart, would like to earn God’s approval. His gift is one of pleasing God himself, of entering divine fellowship on the merits themselves.

The Master wastes no time in having none of it.

In plain allegory that would make John Bunyan proud, Herbert kicks off the poem’s brutal gauntlet.

The servant instantly

Quitting the fruit, seiz’d on my heart alone,

And threw it in a font, wherein did fall

A stream of bloud, which issu’d from the side

Of a great rock: I well remember all,

And have good cause: there it was dipt and dy’d,

And washt, and wrung: the very wringing yet

Enforceth tears. Your heart was foul, I fear.

Stanza two brings similar treatment.

Here, the speaker’s heart is thrown in the cauldron of ‘Affliction’ where it expels a foul liquid—a scalding purification to go with the cleaning. Here again, Christian allegory goes to work; hardship and affliction purifies the soul, distilling genuine, long haul faith from base, impure motives.

But that doesn’t dull the yearning, or make the unexpected pain any less shocking:

But as my heart did tender it, the man,

Who was to take it from me, slipt his hand,

And threw my heart into the scalding pan;

My heart, that brought it (do you understand?)

The offerers heart. Your heart was hard, I fear.

Indeed it’s true. I found a callous matter

Began to spread and to expatiate there:

But with a richer drug then scalding water

I bath’d it often, ev’n with holy blood.

Herbert keeps Christ’s sacrifice close at hand. The ‘richer drug’ that supples hardness is, of course, the ‘holy blood’ shed for him.

In stanza three, the exhausted speaker retires to bed, only to find it laid with thorny ‘thoughts’ that pierce his heart. Wearied, aggravated, and unable to sleep his miseries away, rest, Herbert prays nonetheless.

Even though his heart is not in it.

Indeed a slack and sleepie state of mind

Did oft possesse me, so that when I pray’d,

Though my lips went, my heart did stay behind.

The whole journey takes a shape that most of us—and some more than others—know too well. Opening our hearts to love, give, serve, and hopefully see those things reciprocated, makes us a sitting duck. All good, sacrificial love (not the same thing as heart yearning) comes with pain and loss, the only question being when. Without intending to, Herbert’s vision of a heart going through the meat grinder paints a picture that every heart knows.

People disappoint, or pass away.

Hopes, dreams, achievements, even new beginnings —at one point or another everything’s moth-eaten. Building on this, the poem cuts hard, and then harder, until we turn the corner for a tender ending.

As Herbert tells it to himself, we realize it was coming all along.

Truly, Friend… mark the end.

The Font did onely, what was old, renew:

The Caldron suppled, what was grown too hard:

The Thorns did quicken, what was grown too dull:

All did but strive to mend, what you had marr’d.

Herbert’s devotional turn is no great mystery. Dare I say, it’s also not possible in a Godless universe, one where ultimately meaningless heart yearning and disappointment play us like marionettes.

But for those who know, and trust the creator Himself, Herbert’s final refrain is less of a parable and more of a call to worship—and even, though it might sound masochistic, a note of gratitude that God himself (who should be the object of our heart yearning, but rarely is), allows pain and suffering.

The Christian’s truth claims are not vague on this.

As on the cross, and in our loves, God explicitly, and for purposes that serve His ends and prepare us for our great joy as eternal beings, allows longing. Heartbreak. Disappointment. Even physical, though temporary, death. Of course, in allowing these things, he gives us the mean of drawing close to him, our rock and our portion.

Painfully washed and suppled in affliction, heart disappointment guides us only to him, into other’s arms, and into being the arms others need ourselves.

But that’s not everything.

Herbert reminds us that there’s one more, if rarely discussed purpose to affliction, pain, and heartsickness—keeping us primed and alive for joy and pleasure, of unimaginable scope6.

Herbert captures this in rhyme, and in fewer words than Saint Paul himself:

Wherefore be cheer’d, and praise him to the full

Each day, each houre, each moment of the week,

Who fain would have you be new, tender, quick.

Here, at the end of a heart gauntlet, we’re tilting on mirth.

The pain smarts, and the heart groans.

But on the other end, the one his volumes of poetry speak too, a party—rather, a wedding banquet—is just ramping up. It’s the deepest, richest answer for a thousand heart different yearnings, for each heart needs different things.

But Christ rising from the dead promises one thing: in Him, at a point in linear time, no heart will be left wanting.7

That’s the promise, and one thrilling reason for life’s gauntlet doing what it does. Another caveat, and one the C.S. Lewis explores brilliantly in The Great Divorce, is that in the end, like Philip ducking out on his graduation, what we think we want won’t have been what we really wanted.

In effect, some pain and affliction might be the retroactive blessing of having not given us our own, stubborn way.

There you have it

Still, what a gauntlet… even if it’s not the full, fiery gauntlet that dying on the Cross was to a sinless, innocent God Himself. if only an echo of the fiery gauntlet that dying on a Cross was. It’s not for nothing that the servant in the poem intercedes for Herbert, handling the heart and preparing it to be new, tender, and quick enough to please both the speaker and the master.

With wit, brevity, and unwavering devotion to his subject, Herbert wrestles the heart’s selfishness and wins. In place of yearning and identity as 'capital G' gods, Herbert shows us beauty, self-forgetfulness, and the emotional depths of the Christian walk.

In one poem, he also grows wings.

Herbert, like Shakespeare, and even like Maugham (on accident), tilts our chins up to the Heavens and beyond ourselves, where the best, and only final hope exists.

Emily Dickinson, ‘The Soul Selects Her Own Society’

W. Somerset Maugham, ‘Of Human Bondage,’ Chapter eighteen

W. Somerset Maugham, ‘Of Human Bondage,’ Chapter Nineteen

W. Somerset Maugham, ‘Of Human Bondage,’ Chapter Nineteen

W. Somerset Maugham, ‘Of Human Bondage,’ Chapter Twenty-One

Revelation, Chapter 21

Gospel of John, Chapter 9: 10-11

So profound! Thank you for writing this!

I’d love to dig a bit deeper into this topic, but I don’t want to be out of my depth 😅 do you have any recommendations? If not it’s okay! Your writing on this aspect of life just struck a chord in my heart. I’m a Reformed Christian, if that helps for even 1 recommendation! 🙂