It’s looking like the tragedy of Lahaina, and for all of Maui’s residents was, to some degree, preventable.

Investigations into island officials, decision-making, and Hawaiian Electric, the utility company responsible for ill-maintained infrastructure that likely sparked the deadliest fire in recent history, are all underway.

Maui’s top emergency official already resigned.

But as with every other, seemingly unrelated catastrophe in the news, there’s a dormant lesson we’d rather talk about.

You may know where this is going, but if not, bear with me—and if you’d rather jump to memes, or to D.T.’s fine column on how we think about the environment and our role in it, scroll on down.

To Stop a Fire, Check the Landing Gear

In an interview with speechwriter Peter Robinson1, economist emeritus Thomas Sowell recalls a near-accident he experienced while flying into New York’s Ithaca airport.

Within a hundred feet of the runway, the pilot suddenly gunned the engines. Instead of landing, the plane swerved back into the air. Later, Sowell learned that the pilot had forgotten to lower his landing gear. Someone in the control tower—a nameless Joe simply doing his job—caught the problem and told the pilot to pull up.

Here’s the clip of Sowell telling it.

The full interview (also worth watching) is about his book ‘Intellectuals and Society.’ The Ithaca Airport story comes out to illustrate what Sowell calls ‘consequential knowledge.’

That is, knowledge whose presence or absence has consequences.

Right on the heels of this, Sowell drops something else. In any society—not in the least an advanced, integrated one covering two billion acres and housing three hundred-thirty million people—it’s far easier to concentrate power than knowledge.

Unlike power, and by its cumbersome, seemingly mundane nature knowledge is diffused. It’s spread out, scattered across a population in bits and pieces that have little value in the aggregate, but immediate, life-or-death relevance to those on the ground—and to the likes of Facebook and data harvesters, dollar value.

Writ large, complex systems like a bank, the housing market, or Maui’s disaster response all rely on people—systems of people applying their bite-sized knowledge in respective spheres consistently. Someone in the control tower watching planes land is one small example. Complex systems function with everyone’s combined competence, and on the general bet that if someone has a job, they have the knowledge and wherewithal to do it reliably.

It means we know less, and rely on much, much more, than we realize.

As Sowell points out, stepping a few inches outsides limited expertise means coming to a cliff—or even worse, not knowing a cliff is there. Not knowing the landing gear isn’t down—or that Hawaiian Electrical, (like PG & E in California) was woefully behind on power line maintenance and brush clearing going into a dry, windy time of the year—brings serious consequences. Power, with its totalizing capacity, can easily constrict that flow of knowledge, bringing systems to a halt for arbitrary, if generally convincing reasons.

In the old Soviet Union, centralized power preempted hundreds of millions of people constantly, with sad but nonetheless laughable examples. As the adage goes, a machine shop owner calls his boss in Moscow: ‘you ordered green tanks. We have tanks, but no green paint. Can we use the red paint we have in stock?’

The boss—no doubt intelligent, but fielding thousands of questions like that a day—says ‘hold on.’

Three or five months later: ‘Yes, red paint is fine!’

Right up to collapse.

Put Another Way

A good friend and I taught English in the Sacramento area. He taught (and still teaches) seventh and eighth grade in the city. For a stretch beside him, I taught sophomores and juniors in a small, college town.

We talked shop, comparing school and teaching quite a bit. We shared plenty of detail on the books we used, methods we were trying, challenges with particular students, and on thoughts on admin, colleagues, paraeducators, our student’s parents.

Think about it: same profession

Same subject, interest, state, region.

On the whole, same approach to classroom management.

If he and I ever swapped places, both of us would both be completely lost… for a day or two, if not for a couple months.

From the bell schedule to homework policy to classroom layout, and not even counting the lessons, curriculum, interactions with staff and each class’s energy, personality—the gaps in consequential knowledge, necessary for any hope of smooth sailing, would take time to make up.

At the same time (and until I left after 2018’s Janus ruling) our union dues, like the dues of some three hundred thousands teachers in California’s public schools, went to the same, relatively small group of shot callers. The CTA, the NEA, and their smarmy allies in the state’s Democrat legislature and Jerry Brown (now Gavin Newsome) administrations.

When I left the unions, I asked my local union rep if I could chip in personally for the work his team does (bargaining with the district and so forth).

After checking with the higher-ups, he said no.

Power is easy to concentrate, hard to diffuse.

But the good news, as Sowell points out, is that in a free-market society with minimal-if-necessary central power, nobody needs to know everything. No elite group needs to pretend it has enough knowledge to things better than millions of everyday people. The everyday people run circles around them, just by addressing what immediately concerns them with ability, consistency, and entry-level competence.

At least, that was the assumption.

How Systems Collapse

Enter diversity.

Anti-racism.

DEI.

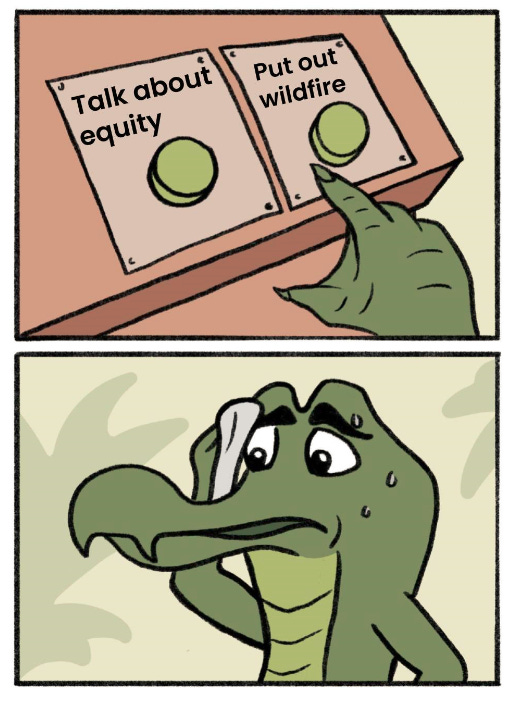

Enter Obama-appointed Department of Land and Natural Resource czars who winge about equity one day… and then hold up Maui’s fire response the next (Apparently, when you’re dealing with taro farmers, and honoring water’s sacred animistic value, wildfires take a timeout).

I could be wrong, but I doubt that M. Kaleo Manuel diverting said water after balking at the idea and then stalling for time is any consolation. Not when it didn’t arrive in time.

C’mon. What’s incinerated towns, a hundred dead, and over a thousand missing next to a true conversation about equity?

Enter woke thinking, with the general notion of categorizing people by race, gender, and tribal culture, and then promoting people via said categories as a nod to past wrongs, perceived discrimination, your own benevolence, historic struggle, or what have you.

Inject that ideology into the complex, interlocking systems of the world’s largest, merit-and-ability built economy, and what do you get? What happens when we stock complex systems, designed to run on competence with the semi-qualified (as opposed to most qualified), and reasons other than their competence? California, Portland, The Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Bud Light, the U.S. Military, and now all of Maui might very well ask.

Meanwhile, you got front row seats to an experiment.

You get Afghanistan.

Southwest cancellations.

Ports like Los Angeles becoming gridlock.

Trains derailing and spilling chemicals all over a small town in Ohio.

Fast moving wildfires, burning unopposed and swallowing towns.

If you push it all far enough, you get the power failures, riots, and spiraling chaos of a South Africa.

As a bracingly honest article in Palladium puts it, complex, interlocking systems designed to run on diffused knowledge and competence start to fail. When one system starts to fail (say, a housing market propped up on bad loans), it crashes into another like a row of dominoes.

As author Harold Robertson puts it:

“America must be understood as a system of interwoven systems; the healthcare system sends a bill to a patient using the postal system, and that patient uses the mobile phone system to pay the bill with a credit card issued by the banking system. All these systems must be assumed to work for anyone to make even simple decisions. But the failure of one system has cascading consequences for all of the adjacent systems. As a consequence of escalating rates of failure, America’s complex systems are slowly collapsing.

The core issue is that changing political mores have established the systematic promotion of the unqualified and sidelining of the competent. This has continually weakened our society’s ability to manage modern systems, and it’s a break from the trend of the 1920s to the 1960s, when the direct meritocratic evaluation of competence became the norm across vast swaths of American society.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, the idea that individuals should be systematically evaluated and selected based on their ability rather than wealth, class, or political connections, led to significant changes in selection techniques. Spurred on by the demands of two world wars, this system of institutional management electrified the Tennessee Valley, created the first atom bomb, invented the transistor, and put a man on the moon.

By the 1960s, the systematic selection for competence came into direct conflict with the political imperatives of the civil rights movement. During the period from 1961 to 1972, a series of Supreme Court rulings, executive orders, and laws—most critically, the Civil Rights Act of 1964—put meritocracy and the new political imperative of protected-group diversity on a collision course. Administrative law judges have accepted statistically observable disparities in outcomes between groups as prima facie evidence of illegal discrimination. The result has been clear: any time meritocracy and diversity come into direct conflict, diversity must take priority.

The resulting norms have steadily eroded institutional competency, causing America’s complex systems to fail with increasing regularity… either selection for competence will return or America will experience devolution to more primitive forms of civilization and loss of geopolitical power.”

Assuming you read that… or that you hopped over to Robertson’s superb article, which way do we go?

Which way, voters? Shareholders?

Board members, and interview panels?

Hate to say it, but which way, voters in deep blue Maui?

Between a merit, knowledge, and ability based system that unlocked more growth and opportunity for its participants than any other in history—including, if imperfectly, those very groups DEI purports to represent—between that system and the tried and true practice of everyone hiring their first cousin (or at least a member of their tribe), which way indeed?

In the Memetime…

If you haven’t seen Oppenheimer, here’s our warning.

Bring earplugs.

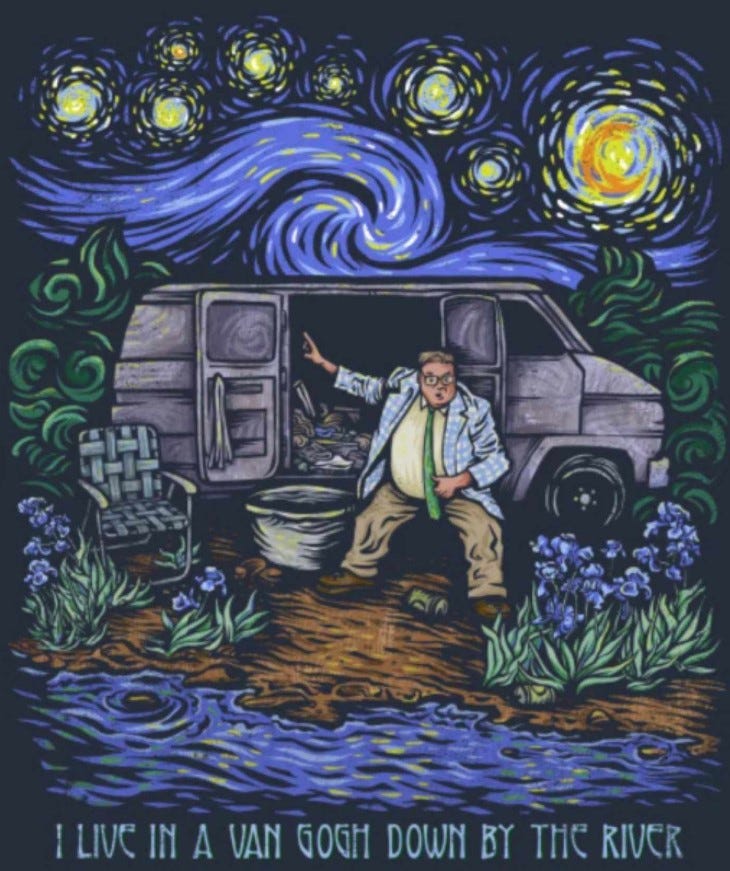

San Francisco, of course.

Big Sister is watching you.

The Environment: Preserve or Cultivate?

by D.T. Adams

When I visited a picnic area on Mount Rainier, there were signs all over the place telling you where you couldn’t go. One quickly got the feeling that they were a visitor, welcome only at certain times and for acceptable reasons (and a fee, of course).

With some in the media blaming the recent Maui fires on climate change and President Biden’s decision to preserve nearly one million acres of land, the environment has been on my mind. The President mentioned “preserving these lands…,” which got me thinking about my experience in the Mount Rainier National Park. While the stated purpose of this land designation had more to do with Native American (is that still the right term?) history, the media just can’t help themselves. The climate gods might get angry if they don’t pay their due homage.

The underlying assumption of most of the discussions I see around both of these events is that people think humans are always a negative influence on the environment; therefore, we must work to keep people out of those places we want to designate for their natural beauty and variety. Instead of incentivizing a responsibility in each household to cultivate the natural resources and beauty of their land, we segregate beauty and wildlife into designated areas.

It’s as if they’re saying, “Let’s keep people away from as much of the earth as possible because we all know that humanity’s primary influence on its environment is negative.” It’s the invasive species someone introduced, the carbon emissions from cars, the flatulence of cows raised for people to eat, etc., etc. The underlying message seems to be that if there weren’t so many darn people around, the world would be better off. Then, the same people organizing these preserves and leading these climate initiatives pay someone to landscape their property, often using harmful herbicides and pesticides.

But is there another philosophy that might provide a principled environmentalism that doesn’t view humanity as a planet-wide infestation?

Keep Nature Out in Nature, Not in Our Yards

“We have lived our lives by the assumption that what was good for us would be good for the world. We have been wrong. We must change our lives so that it will be possible to live by the contrary assumption, that what is good for the world will be good for us. And that requires that we make the effort to know the world and learn what is good for it.”

I can’t help but wonder if the segregation mentioned above isn’t the best path forward. Why not seek some balance? There are ways to farm, garden, and landscape that, while not resulting in as pristine of a setting, are better for the people, plants, and animals involved. Why not let each household cultivate the beauty of their property?

This begs two questions: “What about the astronomical price of real estate?” and, “Isn’t that the government’s job?” First, that’s the beauty of this appreciation of beauty: you can do it nearly anywhere. If you live in a high-rise apartment, it’s possible to have a small variety of plants on your patio or windowsill. There are plenty of guides for growing things in urban situations. And if you’re unable to plant things in the ground because you’re renting, there are a variety of options for growing plants in containers, big or small. And regarding the second question, even if you’re unable to grow something at home, most of us could be much more involved in our city and county land development decisions than we are. We’ve seen relatively recently the government’s level of competence when it comes to environmental issues.

My point isn’t that we must all be doing all of these things; quite the opposite, actually. My argument is that there are a number of ways for each of us to be involved in our local environmental decisions and that these decisions should not be informed by trying to keep people out of as much of that land as possible.

Mankind: Asset or Liability?

Instead of viewing people as liabilities or negative influences on the environment, is it possible to encourage people to be positive forces? People, although capable of harming their environment, are also capable of cultivating it. Farmers like Joel Salatin and Wendell Berry are prime examples of farmers taking the environment seriously, although it looks quite different than some of the most vocal “climate activists” might like it to. Most climate alarmism seems political and purely meant to stir people up into a religious fervor, ensuring they vote for certain candidates. It’s clear that people need to know how to interact with the environment, but that requires knowing our place in it.

Christianity provides this grounding: God has made mankind the ruler over creation for the good of both humanity and creation. Is human action a primarily negative influence or a positive one? Christian philosophy would say that, when people are acting as God commands, they are a positive influence. In fact, Christian philosophy would say that one of mankind’s primary purposes is to be a positive influence on the environment.

This begs all the begs the question: which philosophy is better for both people and the environment?

Peter Robinson was a speechwriter for President Ronald Reagan; he’s credited with writing the ‘tear down this wall’ speech.

The Van Gogh thing was awesome! Could you let me know where exactly in San Francisco this is located? I'm planning to check it out the next time I'm there. On a more serious note, when it comes to preservation, the issues of reforestation and re-wilding immediately come to mind. Often, the planting of trillions of trees becomes a major headline, yet very few are focusing on stopping deforestation. Similarly, the Silicon Valley mindset provides people like George Church with millions of dollars to revive woolly mammoths (https://www.cnbc.com/2021/09/13/geneticist-george-church-gets-funding-for-lab-grown-woolly-mammoths.html) However, I work for a natural history museum where we are struggling to find, train, and support taxonomists and data scientists to understand and preserve endangered species. But I agree that "there are a number of ways for each of us to be involved in our local environmental decision".